Liminal: an adjective to describe a transitional stage or something on a boundary ‘Liminal’ has long been a favorite word of mine. It always reminds me of the colored bands … Continue reading

Liminal: an adjective to describe a transitional stage or something on a boundary ‘Liminal’ has long been a favorite word of mine. It always reminds me of the colored bands … Continue reading

When I was little, I had a fluffy, white, stuffed animal cat named Crystal. She was a favorite toy and a constant companion. I traveled with her, made up stories about her, and no matter where I was I could drift easily off to sleep if she was with me.

To this day, I vividly remember a nightmare I had about Crystal years ago. As I held her to my chest, she transformed into a hideous cartoonish villain. Her round blue eyes narrowed to red slits. Her sewn mouth opened to a jeering grin filled with venomous pointed teeth. Her soft white fur bristled and darkened, and her huggable body was all angles and arches as she took in a breath to hiss evilly at me.

I woke with a fright and kicked her from my bed. Gasping with fear, I struggled to disentangle dream from reality. It took a long time of suspiciously watching Crystal out of the corner of my eye—in the light of day, of course—before I trusted her enough to let her back onto my bed. That one frightening image was burned into my mind. It over-wrote years of happy memories, and my unquestioning trust that my favorite stuffed animal would always be gentle and comforting.

For some of us, our relationship with the Lord can have frightening parallels to my *melodramatic* childhood experience. We know that God’s character never changes,1 but for various reasons our understanding of God can undergo frightening or even traumatic change.

Unfortunately, a changed view of God can be forced on us—like a horrific nightmare we didn’t choose. In Scripture, God compares himself to a king, a father, a mother, a shepherd, a husband, and other roles present in our daily lives. If those types of people have harmed us in the past through abuse, neglect, or other distortions of their God-given relationships and leadership, they have changed our fundamental understanding of that role. And in turn, our understanding of who God tells us he is can be broken.

With enough time and repetition, our body and minds can be ‘rewired’ to hold that trauma. If we have been spiritually abused by a mentor or spiritual leader ‘in the name of God,’ the experience can traumatically alter our relationship with God himself. It can take a long time to heal—to sort out the truth of who God is from how he’s been falsely portrayed to us, to understand and believe that God is not dangerous.

I have recently walked through a dark valley of spiritual abuse. I worked in ministry under a boss and mentor I trusted with vulnerable parts of my spirit, and that trust was abused to take far-reaching control of many areas of my life—mental, physical, emotional, spiritual, occupational, social—all of it. No area of my life felt safe or untouched.

With some time and space after leaving the situation, my heart, soul, and body dropped out of the high-adrenaline survival mode I had been in, and the full impact of my experience shattered my spiritual life. This fallout is common to those who’ve survived spiritual abuse. In the same way that that one nightmarish image of a trusted comfort from my childhood over-wrote what my mind knew to be true, one experience with a bad shepherd can deeply damage a person’s faith in the Lord.

Victims of spiritual abuse experience the same repetitive cycle of abuse that a beaten wife or a rape survivor experience.2 They can struggle to sort out whether their experience was their own fault, and they can feel deeply grieved and violated, as well as immense shame and disorientation. The difference with spiritual abuse, is that what the survivor has experienced has been done to them in the name and under the ‘authority’ of God.

In cases of spiritual abuse, Scripture can be twisted to falsely condemn or control. The victims can feel strong guilt for disappointing their spiritual leader and breaking his or her rules, and often have been groomed to believe that such conduct is sinful even if scripture confirms no such thing. Victims of spiritual abuse fear leaving or speaking out against the abusive treatment because they’ve been manipulated to assume that no one will believe them. They fear that speaking out will lead to spiritual exile and rejection from their faith community. And they have to sort through all of these feelings often while they still can’t shake the internal and external accusations that control and keep them in fear.

At the beginning of my journey towards healing from spiritual abuse, my faith was shattered. Many times I was physically unable to open my Bible to seek comfort and truth in the Word of God that had so often been my most trusted anchor. I shook violently with anxiety in church settings and other religious gatherings. Prayer felt impossible because God felt dangerous. I couldn’t erase the angry, unsympathetic, vengeful, domineering, oppressive image of God that my abuser had modeled for me. Instead of the Good Shepherd I knew I would find in Scripture, all I could feel, believe, or imagine was a hired hand who looked after the sheep under his care only second after his own image and well-being.3

Whatever life experiences may have led you to feel this way, try as we might, the faith that we long to catch us, and the Good Shepherd we long to cradle us in our brokenness feels dangerous and unapproachable. Often no amount of logic or Scripture reading can enable us to muscle through what our nervous system screams at us is unsafe. When we try to pray or read our Bible, our bodies and minds can viscerally refuse, and we long to kick the danger away, just like I did after that childhood nightmare.

In all of our pain as we walk through spiritual abuse and the healing on its other side, we struggle to shake off the twisted ferocity of the ‘god’ our abusers have taught us relate to. This can be further complicated by God’s sense of justice that we see throughout Scripture. We know that his anger towards sin is fierce, and often our abuse has habituated us to assume that anger is directed at us. We struggle to reconcile those oppressive feelings with the mercy and goodness of God. What we cannot see, feel, or believe is that God is a good shepherd toward us—that he cares for our health and healing and rejoices when we turn to him.4

Though it can be hard to see the light at the end of that tunnel, it is faith in what we hope for5 that can slowly pull us through. We must desperately hold onto our memories of a good God who was a good shepherd to us, and pray it to be true.

And like the Good Shepherd that he is, the Lord will provide for our needs. He longs for us to draw near. He longs to bind up our wounds.6 He longs to sing and rejoice over us.7 We who have been spiritually abused fear a distorted image of God’s sense of justice. But the direction of that justice can be part of our healing: God cares most fiercely for the oppressed, the ‘lost sheep,’8 and the vulnerable.

The meekness of Jesus has been the greatest drive behind my healing: in his strength, he chooses to be gentle, and with his power, he chooses to protect. With all the power in the universe at his command, and all the needs and desires of the crowds clamoring for his attention, he chose to welcome humble children.9 His fierceness is often directed at spiritual leaders who mislead or complicated access to God for those under their care.10 At his angriest, when he flipped tables in the temple, he was furious that anyone would hinder those who wished to come to God in prayer.11 And he says that the consequences for anyone who causes someone young in their faith to stumble are worse than having a millstone tied around their neck and being thrown into the sea.12

If the spiritually abused are sheep who have been spooked and fear their Good Shepherd as a result, our God does not abandon us until we can return to the flock on our own. As a Good Shepherd, he responds to us with tender care. He comes to seek us out and restore us.13

And as he heals us and restores our faith, we often can look back as the Israelites did14 on our greatest stories of rescue. It is when we are lost and most desperately in need of a savior that our God acts in ways that teach us most to know and trust his good character. He gives us new memories that prove his goodness and trustworthiness.

If you are struggling through a season when God feels dangerous, I deeply sympathize, and I sit with you, brother or sister, in the grief and brokenness. I am immeasurably sorry for the harm you have experienced in the name of the Lord, and I pray that he will slowly and gently embrace you with his true character as you heal.

There is hope and help for your healing. If you are able, I encourage you to spend time reading the Gospels to learn how Jesus responds with gentleness and care to the people around him. Relearn his character.

A Christian counselor, especially a trauma-informed one, can help you immensely in your healing process. There is also much to be read and listened to that can help you understand your experience with spiritual abuse. Diane Langberg, K. J. Ramsey, and others are such trauma-informed counselors, and their writings and discussions in any media are helpful on these issues. Plenty of podcasts dive into these experiences as well, ranging from The Rise and Fall of Mars Hill, which dissects a prominent instance of spiritual abuse, to episodes of the Allender Center Podcast, which discuss the mechanics, progression, and healing of spiritual abuse. The Common Hymnal and Porter’s Gate produce worshipful music that speaks specifically into these types of brokenness.

But even stories or books that obliquely reference gospel truths are helpful in your healing. The Lord of the Rings, The Chronicles of Narnia, and plenty of others can be instrumental in your healing as they can slowly walk you back to the divine realities of redemption, hope, and restoration through their reflections in the world and literature wholly separate from the Scriptures and contexts in which you were wounded.

Great healing can also come from Christian community around you. People who can speak these scriptural truths into your life, who gently share verses or stories with you when you can’t take them in on your own; brothers and sisters to walk with you and carry you to Jesus when you can’t move on your own—this is the Body of Christ that can surround you and be the hands and feet of Jesus to you as you slowly relearn that your Good Shepherd is not dangerous.

1 Hebrews 13:8

2 https://www.verywellhealth.com/cycle-of-abuse-5210940

3 John 10:1-18, Ezekiel 34

4 Luke 15:3-7

5 Hebrews 11:1

6 Psalm 147:3, Ezekiel 34:16

7 Zephaniah 3:17

8 Matthew 9:36, John 10:1-18

9 Mark 10:13-16

10 Luke 11:37-54, Ezekiel 34

11 John 2:13-17, Matthew 21:12-13

12 Luke 17:1-2

13 Matthew 18:12-14, Ezekiel 34

14 Psalm 136

Content warning: This post addresses endemic sexual and spiritual abuse within Southern Baptist churches. No graphic descriptions are given, but please care for yourself if this content could be triggering.

Many of you have at least seen this week’s headlines about the Southern Baptist Convention (SBC). Southern Baptist churches are loosely autonomous, but united under the SBC and the same understanding of doctrine. The SBC and its organizations range from church planters in the States (North American Mission Board—NAMB), to missionaries and church planters overseas (the International Mission Board—IMB) to the Southern Baptist Seminaries and State conventions of cooperating churches in most of the 50 States.

If you have read the news this week, you have learned of the horrific extent to which spiritual leaders have abused those under their care. Those who were meant to be shepherds, instead of caring for their people have directly abused them or covered up for those who did. Not every pastor or every church has been implicated, but the shocking numbers from a third party report indicate that many more of us have been touched by this egregious sin that we would like to believe. If you would like to read the full report, you can find it here, as well as the actions proposed by the investigation team.

I have a particular stake in this endemic abuse. While I have not been sexually assaulted by a Baptist leader, I have been in the petri dish that provides a nurturing environment for abusers. I have both experienced great abuse and brokenness within the SBC, and great healing and care. If you are tempted to breeze past these headlines, to wonder why they’re important to you beyond this week, I want to tell you. If you have experienced abuse and lived in the dark with it, I am so very sorry. I want to speak up with you and stand by your side when you cannot speak.

Too often, to our shame, abuse survivors are pushed to the side. Their stories are silenced or muffled, or worse, discredited and ignored because their words are ‘divisive’ or ‘hyperbole,’ or perhaps because they’re seen as a radical whose beliefs do not align with most Baptists. If my experiences and my history mean anything to you, if they help you sympathize with abuse survivors or recognize the lifelong consequences of abuse, I will share them. If the platform I stand on helps you listen or understand, I will use it.

I was born to Southern Baptist parents, and even after multiple moves I have only ever been a member of Southern Baptist churches. SBC summer mission camps led me to follow the Lord to the mission field overseas and in the States. I have faithfully attended, volunteered at, spoken, and taught in these churches, and worked for nearly 6 years overseas with the IMB. But more than those facts can show, Baptists have been home for me. They have prayed for me, fed me, paid my salary, and been my family. They have discipled me and held me while I healed. I have come to know the Lord and follow him in obedience through a Southern Baptist lens.

But I have experienced sexual harassment and mild assault while performing my job with the SBC, and many of my claims were ignored or handled poorly. I was asked not to speak openly about these experiences for a variety of reasons. I have experienced specific instances of discrimination from IMB leadership, both as a woman and as an unmarried person. I suffered sustained emotional and spiritual abuse from IMB leadership, and experienced retaliation and reprisal as a result of reporting this abuse. And while some of my concerns were heard and responded to in the end, the hurt and trauma are not erased.

I bear these emotional scars, and they run deep enough to affect the rest of my life. Like Paul when he ‘foolishly boasted’ to the Corinthians, I share these facts not out of pride or desire for respect or notoriety. I foolishly speak of these things to this end: I wish for you who read this to understand that my words are written here not out of a spirit of malice or a desire to sow disunity. I want you to know that my eyes see the decaying roots in the SBC, my experiences help me to understand it, and my memories still feel the rot.

I still have tremors in my hands when I walk into a church. The part of me before who could speak freely and movingly to a congregation has been quieted and replaced by a dry-mouthed and fumbling speaker, unsure and shrunken under the gaze of men and women whom my mind will no longer allow me to instinctually trust. I have questioned many times whether I should leave my work in the hands of others and abandon what feels like a sinking ship. I have fought with my conscience time and again over the ethics of my paycheck. And I have stood my ground with the support of other Southern Baptists to leverage my experiences for the sake of repairing that sinking ship.

To any of you who have left the SBC denomination because it is no longer safe for you, to any who have stepped aside from churches at wide because they have not healed from damage and hurts, to any who see the apostasy, hypocrisy, or corruption of the SBC and their consciences will no longer allow them to stay: I understand and stand with you. I sympathize and empathize. The Lord will give us all convictions, and obedience and self-protection can look different for each of us.

But to those of you who stay, you need to understand what an abuse survivor may have experienced. Unfortunately, sexual abuse is part and parcel of power abuse at large. Believers still sin, and those far from the Lord and walking in sin can fall into patterns of abusing whatever influence or control they hold. This love for power is the same root underneath racism, sexism, discrimination, spiritual abuse, and emotional abuse in our churches. And if any of you are completely shocked that such abuse could happen here—in our fellowship halls or youth rooms—you have not been listening to the voices of your brothers and sisters with different shades of skin who have cried out about the mistreatment they’ve experienced from behind our pulpits. You’ve chosen to look aside from the smaller paycheck the women or divorcees on church staff receive compared to others. You’ve failed to recognize when singles are understood to be less spiritually mature than married individuals on principle.

If you have missed these signs of abuse or neglect, there is plenty of time to open your eyes to them and recognize that they are not accidental or isolated incidents. You have plenty of time to turn your eyes to your wounded brother on the side of the road instead of walking by. These reports show clear patterns of abuse across our denomination, and the safe assumption right now is that you know other church members who’ve been abused, and that your church could do better in preventing or caring for abuse victims.

To let these headlines pass you by without evaluating your actions is tantamount to what David did for Tamar. After David’s illicit sex with Bathsheba (arguably rape), it took him some time to see his sin. When he did, he repented and married her, but that was not enough to bring her husband back from the dead, or to save their baby from death. Later on in David’s life, his greater love for his sons, or his own hesitancy to hold others accountable for mistakes he felt capable of making himself, kept him from caring for his own daughter Tamar when she had been raped by his son. That sin festered all the days of their lives. Tamar lived alone and abandoned. Her rapist was murdered by a half-brother who’d fruitlessly urged David to take action. And the half-brother murderer soon claimed David’s throne for his own and exiled his father, before the son’s tragic death and David’s overwhelming grief. Abuse festers. When we are tempted to ignore it, only exponential hurt can come from that path.

Because of the manipulation inherent to abuse, many survivors like myself still struggle to tell their story without still wondering, in their heart of hearts, if it wasn’t their fault. And telling their story can be painful, often because in the SBC environment we live in, the risk of not being believed and the consequences that would follow are just too great. Will they be fired from their jobs? Lose their standing in the church or community? Will they be blamed for disrupting peace? Will they lose their church family altogether and be looked on with mistrust until they finally leave the church voluntarily?

Those are all fears and consequences we have in our hands to change. By denouncing abuse openly, we set minds at ease who fear revealing it. By aligning ourselves more with the kingdom of God than any political or administrative kingdom, gender or skin color here on earth, survivors can trust us more to treat them with the compassion and healing Jesus would. By openly expressing support for abuse survivors, over the SBC or a particular leader or ideology, we show our value for people made in the image of God. If we truly value each person made in the image of God the same, we owe abuse victims the dignity of valuing them with urgency when they have suffered so great a spiritual, physical, and psychological blow.

Many abuse victims, myself included, have been answered with the subtly destructive phrase, “let’s keep the main thing the main thing,” or its variation of “We need to put the gospel first.” But recognize with me, church, that the gospel is not just a message of Jesus on a cross and heaven eternal. The gospel message was embodied in Jesus, whose kingdom values compelled him to welcome women as well as men in his closest circle of followers. The gospel compelled Jesus to provide care for his marginalized mother even as he was dying on the cross. The gospel compelled Jesus to stop his teaching and welcome little children to him. The gospel compelled Jesus to stand between a woman accused of adultery and to take on her case and shame in the eyes of her accusers. Jesus himself said he came to call out good news to the poor, to release prisoners, give sight to the blind, and set free the oppressed. And those weren’t metaphors or solely spiritual realities. Who else are victims of abuse but the poor in spirit, those blinded in the dark by their isolation, prisoners of lies, oppressed by their abusers?

Church, the gospel IS the main thing, and it compels us with every fiber of our being to be a balm to the hurting. And that includes those abused in our church buildings and by our pastors and leaders.

So how am I with all of this? This week has been a hard one. With every next piece of news, both my mind and body have to process through tension, grief, anger, humiliation, helplessness, devastation, and so many more emotions. The grief is so fresh and deep that some days I feel like I’m right back in the middle of what I experienced. Many others who have suffered church abuse are experiencing the same things. Plenty of you have reached out to listen and encourage, and I have been more than happy to talk with many of you as you process and understand what this means to and for you. I still have plenty to learn myself. But for now, I feel convicted to stay with the dumpster fire and help put out the flames. Having been burned a few times myself, maybe I’ve learned how to help suffocate the fire in the process.

This very Sunday as I stood trembling in church, praying for the Spirit to overpower my anxiety and help me to worship and learn, the congregation started to sing “He Leadeth me.” In the few churches or groups I’ve spoken to since I’ve been stateside, the ones who’ve reacted most powerfully to what they have heard were the ones I told my personal story to. When I revealed some of my deeper hurts and how the Lord sustained me, others connected to stories of their own and the Spirit connecting us was a strong encouragement. As I sang that song in church, I sank into my seat and fell into a silent prayer. I recognized that the Lord had led me to and through my experiences. He led me out the other side not quite the same Caroline who went in, but with a story to tell and a burning desire to see the church comfort her abused and broken brothers and sisters.

Later that same Sunday the news broke about the SBC investigation, and the Lord had already answered my questions for me. I will stay and be a safe person for others to come to. I will keep in dialogue with those with IMB and SBC already hard at work to help things change. For now and until I hear otherwise from the Spirit. I’ll be the man Jesus healed who was told to stay and tell his story to his village. I’ll be the woman at the well who took a risk and shared her shame so that others could come to know the Lord.

I do not believe that our southern Baptist theology and beliefs necessarily end in abuse. Many Baptists on my path toward healing have proved otherwise. But I do believe that our cultural identity at this point does lend itself to abuse. We have to roll up our sleeves and return to the Word to see how Jesus honors the dignity of the vulnerable and oppressed. We have to keep pressing our doctrines and theology until they meet our practice and show through in all the ways we interact with women, men, and sexuality in our churches; until the pages in our Bible reflect the pages of our lives as leaders humbly shepherd, and use their influence to protect and nurture instead of tear down or feed their own egos.

Those are my convictions for now, and I plan to continue evaluating to make sure I obey the Lord. You might not land in the same place I do, and that’s okay. But for what it’s worth, my opinion is that further involvement with the SBC should be a choice instead of inaction. If you stay, if you move past this news, please do so with the knowledge of the hurting around you. Do not turn your eyes away from them. If you stay, stay with a task and a calling to learn, to rebuild, to comfort, and to change.

If you have caught yourself wondering if this affects you, it does. If your body is diseased, the whole system is compromised. Even a small infection can multiply and damage the whole body. In the same way, a disease in your church, however subtle, affects whether or not your body of believers worships in spirit and in truth. If your church’s handling of this causes even one of the little ones who would come to faith to stumble, it would be better for a millstone to be hung around your neck before you’re thrown into the ocean. Jesus is SERIOUS about protecting his sheep, and he is serious about those in power who could cause them to stumble, or mislead them, or even make the gospel unwelcoming and turn away those who could become little children in the faith.

If you believe this sin is only at higher levels in your church or organization, the same applies: a pattern of sin unchecked at any level is dangerous. As Paul says, an eye cannot say to the hand, ‘I don’t need you,’ and the head cannot say to the feet, ‘I don’t need you.’ God put the whole body together, and there should be no division within it. If one part suffers, every part suffers with it. If we Southern Baptists align ourselves together and understand each other to be a part of the same body of Christ, we cannot ignore a destructive habit in one part of the body and assume it has not manifested in the DNA or cellular level elsewhere.

If you don’t believe that you are contributing to these problematic abusive patterns, you are most certainly enabling them. I say that not to condemn, but to point out that these patterns that allow abuse are ingrained even at the smallest levels. If you are not knowingly and actively working against them, they will continue on, unchanged. If you are not advocating for transparency and safety in your church, if you aren’t praying for the integrity of your leaders, or advocating for their accountability, you are contributing to a pattern in the same way that the religious leaders left the wounded man on the side of the road because they assumed he wasn’t their problem and would be more trouble than he was worth.

If you are one who wants to give grace in situations like these, please recognize the nature of grace. In Ephesians 3 and 4, Paul writes about how we are all united by the same faith and the same baptism. If we believe that, we believe that any Christian is united with any other through the same Spirit of God who lives in them. Paul says that he became a servant of the gospel by God’s grace, so that he could make the gospel known to others and it would unite them. Grace unites and makes whole.

God’s grace isn’t something that spares us from judgment: our judgment still exists, and Jesus suffered it in our place. Grace from God is that Jesus suffered to redeem us to live rightly before God. Grace redeems and restores; it does not turn a blind eye to sin. Grace in the case of abuse holds an abuser accountable so that their sin has consequences and they can learn to live more fully like Christ. And grace for an abuse survivor restores them and treats them with the dignity they have as an eternal bearer of the image of God. As Paul says to the Ephesians, “Each of you must put off falsehood and speak truthfully to your neighbor, for we are all members of one body.” To truly show grace, we must speak truth both to abused and abuser. We must recognize that if sparing a legal consequence of pain for one member causes ungracious suffering for an another in the present or future, it is not grace we show.

The emotional scars that I bear most likely will not go away in this lifetime, before I see my redeemer face to face. Be mindful that there are similar scars in your congregation. Whatever his reason, the Lord has given me the privilege to see many of my own scars begin to heal. He has given me a community of faith that supports me and reminds me through their own actions how the Lord loves and restores. So as often as I can, I intend to wear my scars as a badge of honor to glorify the Lord. Jesus proudly showed his scars to his followers to testify to the Lord’s power over death. Let my own scars show that, as deeply as sin can wound, the Lord can heal even deeper. As much as my scars may ‘disfigure’ my experiences in church or with spiritual leaders, their dull ache will always remind me of the hope I have in a Lord who will heal all wounds and dry all tears.

If you have experienced sexual abuse, please reach out to safe people around you for help, or go to this website for resources or to file a report. You can also call the national sexual assault hotline 24/7 at 800.656.4673. If you have experienced abuse of any kind connected to the IMB, you can call the confidential hotline at 855.420.0003 or email advocate@imb.org .

As I worked through a trauma healing program recently, a partner and I talked about how our heart wounds can be healed, but how they sometimes still leave scars that misshape the tendencies of our hearts for our entire lives.

Later, in a time set aside for lamenting, my spirit was almost too heavy to connect to words. After a time of silence and of trying to pray, I was reminded of one of Job’s laments, and his expression of faith in the lament: “I know that my redeemer lives, and that in the end he will stand on the earth.”

Spiritual abuse is one of those heart wounds or mental/emotional traumas that leaves deep scars. Spiritual abuse is a type of control or manipulation carried out by a spiritual authority, often in the name of God. It ignores the dignity of a person created in the image of God, and abuses power to belittle their spiritual autonomy and control their choices and behaviors. When scriptures are misapplied, when someone claims the authority of God backing their decisions or actions, or when a moral code is enforced outside of what the Bible claims is God’s will and law—those actions, claims, and words slowly begin to reshape the spiritually abused person’s idea of who God is. God can become to them not who they read about in the Bible, but who their abuser claims God to be.

In cases of spiritual abuse, especially ongoing spiritual abuse, the face of God slowly changes into the face of the abuser. And that kind of damage is hard to shake. The best way to heal those wounds is for the abused person to re-learn God’s character for themselves by immersing themselves in scripture. But the nature of the harm done often makes it difficult, or impossible for a time, for the victim to read scripture because it has been abused to wound and control them.

For a very long time, and possibly for a lifetime after the spiritual abuse, the victim will struggle against the ‘character of God’ the abuser portrayed to them. The pull is like a gravity of sorts. In off-guard moments they will hear that ‘voice of God’ or see that ‘face’ as God’s rather than who he portrays himself to be to us in his Word. And that is what I mean by spiritual scars. Just as a child who has been abandoned by a father will often expect God to abandon them as well, a spiritual abuse victim struggles to separate their spiritual mentor’s portrayal of God from the real thing.

I have a poster in my room with an artistic portrayal of the Trinity. It is an absolutely beautiful work of art, and I can get lost in the details for hours. The Father stands above the Son, holding a richly embroidered cloak detailing images from the gospels to drape around his shoulders. And the Son hovers above the Spirit, holding what looks to be the source of a spring of water (welling up to eternal life) which pours out around and behind the Spirit’s head. All three persons have rich, brown skin, kind eyes, and welcoming expressions. But the Spirit is imagined in the art as female, just as the Father and Son are imagined as male.

Any portrayal of God assumes a gender the Bible doesn’t explicitly state. In the beginning, both man and woman were created in the image of God, and neither one is less or more a part of God’s image. God is spirit, and has no bodily gender. God’s character encompasses traits we consider both masculine and feminine. And while Jesus walked the earth in the body of a man, the Spirit of God is often described in feminine terms, with sheltering wings like a mother bird, like an eternal mother who gives us our second birth, like a dove, expectantly brooding over the earth charged with the promise of yet-unborn life. These images are not meant to be a literal description of God just as my poster is not meant to portray an actual form of God. But I found the feminine, nurturing, motherly portrayal of the Spirit to be just what I needed to help rewrite some of my spiritual scars that constantly tug at me to understand the character of God as something twistedly masculine.

Job also had spiritual scars from his ordeal of suffering. After his family died or left him, after he lost his worldly possessions and even the wholeness of his own mind and body, his ‘friends’ lectured him about how he must have wronged God to deserve such treatment. After listening to their interminable prattle, Job lashes out to God, perhaps because he has begun to believe what the friends said of him. In chapter 19, Job assumes God is against him, is waging war on him, and has humiliated, uprooted, and ignored him in his most desperate time of need.

But in the true nature of lament, Job pours out his heart to God and then expresses what he knows to be true even if he cannot feel the truth of it:

“I know that my redeemer lives, and that in the end he will stand on the earth. And after my skin has been destroyed, yet in my flesh I will see God; I myself will see him with my own eyes—I and not another. How my heart yearns within me!”

Even with the pull toward misunderstanding God’s love for him, Job knows that one day his redeemer will stand on the earth for him.

And the text is even more rich than that. The word ‘redeemer’ there is a beautiful tapestry of cultural meanings. It is the word used for someone who buys a person their freedom. It is used for a family member who avenges a death with the blood of another. It is used in Ruth to refer to Boaz—a close relative who chooses to save a family’s name and inheritance by taking a widow as his wife. And a textual variant of this verse in Job calls this redeemer a defender or vindicator. Job knows that one day someone will stand for him, pay for him, remember his story and honor his heritage, and vindicate him against false claims made against him.

Another possible reading of the text says that this redeemer will not stand upon the earth, but upon Job’s grave. Can you see the faith that Job expresses here? In the end, after he is dead and gone, someone will come to stand on his bones to redeem him. Job will not be forgotten or ignored even in death. And he proclaims this truth about a God he has, in the same breath, accused of ignoring and attacking him.

But Job goes on from here into even deeper faith. He says even after his body has decayed, he will see God with his own eyes—he himself, and no one else, will see God in the flesh. A variant of this phrase is “after I awake, though my body has been destroyed, then in my flesh I will see God.” Even when his life hangs in the balance and he does not know if he will live or die, Job knows that one day when he is raised again, he will see God for himself.

And Job is happy about that.

“Oh, how my heart yearns within me.” Goodness. Even when Job feels the Lord has viciously caused the unendurable suffering he has felt, even when he feels accused by God and by man, Job longs for the day when he will be redeemed, when someone will stand for him to remember him and tell his story. And he does not fear the face of an accusing and harmful God on that day. He longs with everything in him to see the face of a God who loves him and who sees only innocence and wholeness because Job has been redeemed from death and suffering.

My own heart brims over with joy at that. I may struggle through this life and its suffering. I may have a scarred understanding of God’s face when it turns toward me. But I know that one day, when I wake from my grave, Jesus my redeemer will stand on the earth. He will vindicate me from false accusations. He will look on me and see innocence and wholeness because he himself redeemed me and my sins with his blood and his life to make me a part of his family. And the face I see on that day will not be disfigured. It will not look like what I have been groomed to believe of the face of God. Oh how I ache for that day.

Some of our spiritual wounds won’t be healed until heaven, and some of our scars may plague us for the rest of our lives on this earth. But that’s okay because we KNOW they will be healed no matter how much we struggle with them now. One day our living Redeemer will stand in victory on our graves, and when we awake we will see him with our own eyes and not the eyes of another. We will be healed and our hearts will be whole.

Our culture of evangelical leadership in the States isn’t fantastic. I don’t know of many who would dispute that we have some problems. People in ministry are often burnt out, depressed, and overworked. Many are put on pedestals and our whole church community reels if they dare to fall into sins that aren’t so far out of reach for many of us. That pedestal and distance from ‘regular church members’ can be a much bigger problem than we realize.

That’s not to say there aren’t church leaders who truly love the people they shepherd, who would give the shirt off their backs to help someone in need. This problem doesn’t apply to everyone, but it is a trait of our culture that can lead to deep spiritual sickness and sin. This influence, improperly wielded by spiritual leaders, can leave deep fractures in our faith community. Words like ‘abuse’ and ‘cover-up’ fill our headlines. Writers and thinkers are discussing the devastation of spiritual abuse for the first time. And many leaders have disappointed us by falling into moral failure or deconstructing their faith and walking away from the church.

The problem comes down to this: we have unwittingly created a celebrity church culture that gives some leaders inherent privilege and power without appropriate check over regular church members. WE have created it, because like the Israelites in the Old Testament, we desire a king. We don’t want to be fully responsible for our own spiritual decisions and well-being, so we appreciate it when someone takes charge over us, leads us, and makes our paths straight. We cede some of our own responsibility for spiritual decision-making and growth over to leaders. And sometimes that gently numbs us into accepting a straight path merely because it’s been paved for us, when instead we should challenge it, or looking to its end to investigate where we’re going.

Leadership and the trust we place in wise elders’ decision-making aren’t bad things. Clearly leadership is a gift given by God to his people to help them mutually grow. The problem comes when the inherent power in that leadership is abused or used lightly, and when we shield leaders from necessary consequences. Some leaders among us reach the end of their public influence or even the end of their lives before the voices that try to hold them accountable can be heard. But the leadership we see in the New Testament is very different that what we find in our church culture.

Jesus himself has quite a lot to say on this matter. In his sermon on the mount (Matthew 5-7), he introduces and describes the kingdom of God and its people. The whole sermon is full of the characteristics of the kingdom, like humility, mercy, and repentance. And one of these characteristics is VERY plain: The meek will inherit the earth.

‘Gentle Jesus, meek and mild’ is a beautiful old hymn. I imagine not many of us know it anymore, nor the rich theology in its verses. But that opening title line sums up the soft, white Jesus with perfect hair that hangs in lots of church Sunday school rooms and stained glass windows. These depictions often paint Jesus as a weak man, who played with lambs and let little children sit on his lap. These portraits, real or imaginary, aren’t often balanced with fiery Jesus, who cursed pharisees, had calloused carpenter’s hands, turned over tables, and chased money changers from the temple with a whip.

Part of our problem seems to lie in the English word, “meek.” It’s not a direct translation from Greek. Meek in our language means passive, gentle, easily dominated, and the connotation, frankly, often means someone meek is kind of a sissy.

But the Greek word we translate ‘meek’ from Matthew 5:5 doesn’t have the same meaning. Strong’s Concordance says, “This difficult-to-translate root… means more than “meek.” Biblical meekness is not weakness but rather refers to exercising God’s strength under his control — i.e. demonstrating power without undue harshness. The English term “meek” often lacks this blend — i.e. of gentleness (reserve) and strength.”

Biblical meekness, you see, is tamed strength. It rebukes the powerful. It nurtures the low and oppressed. It’s a mother bear fiercely protective of, but eminently gentle with her cubs. It is Jesus, the God of the universe, welcoming little children in all their smallness and immaturity. It is humble, patient, loving, powerful, and a mark of the Kingdom of God. Biblical power is meek, and it is protective. Full stop. It isn’t used to get a leg up. It isn’t used to gain position or wealth or more power or adulation. The kingdom leadership we should strive for, according to scripture, is meek. It leads with fear and trembling, but with a sure hand because it is firm in Who it follows after.

Nowhere do we see this balance of tamed power in leadership better than in Jesus himself. As Paul says when he rebukes the Corinthians, “By the meekness and gentleness of Christ, I appeal to you,” let us both desire, cultivate, and become leaders who lead with Christlike meekness.

Jesus teaches his disciples about the necessity of meek leadership in Matthew 18. They ask Jesus who is the greatest in the kingdom, and he takes the opportunity to show them how to be meek leaders through a series of teachings and parables. He turns their question on its head and effectively tells them that it’s the wrong question entirely. He welcomes close some young children and says, “whoever humbles himself like this child is the greatest in the kingdom of heaven.” He says we must become like little children even to enter the kingdom of heaven, and then says, “If anyone causes one of these little ones—those who believe in me—to stumble, it would be better for them to have a large millstone hung around their neck and to be drowned in the depths of the sea.” He is heartbroken over a world with things that cause people to sin and to fall, but he goes on to say that if you are the man who brings those things… woe to you.

I used to assume this passage was about harming and leading children into sin. I still think it includes that, but in the previous quote, Jesus says all who follow him become these little ones. So all his further remarks about little ones include us. Faith by nature is the substance of things unseen; it is not always logical or predictable. Blessed are those who have believed and not yet seen. So, by nature, believers entering into the kingdom of God with such a faith are vulnerable. They know so little of what they believe in initially, that they have to trust teachers not to mislead them as they plunge deep into the words and character of God to learn what exactly it is they have faith in.

Jesus shared this teaching with the disciples, who would soon be responsible with the Spirit’s empowerment to nurture the whole of the Christian world into faith. Jesus tells these men, who would have power and influence: woe to you if you lead one of these little ones to sin. It would be better if we tied a rock to your neck and threw you into the ocean. And that is his answer when they grasp for power and ask who among them is the greatest. He tells them to become low and humble themselves, and follows up by telling them not to mislead a single one of the little ones who will follow after them as they follow after Jesus, or there will be grave consequences.

Proceeding in Matthew 18, Jesus then tells the well-known parable of the lost sheep. He begins with, “See that you do not look down on one of these little ones,” further emphasizing that each little believer is precious and counted by God. Effectively, Jesus tells the disciples that any single person who believes and follows him into the Kingdom is just as important and worthy to be there as the disciples themselves. None are better than the others. He is establishing further principles of leadership. To lead meekly, we must not value ourselves any more highly than a single person ‘beneath’ us, even if they’re as dumb as a sheep that got lost.

The next section of Jesus’ teaching lays out rules for conflict and confrontation. This passage does teach about protecting each other from gossip, but I think we often miss the power dynamics Jesus was teaching about as well. When we read this passage in context and recognize it is part of Jesus’ teachings on meek leadership, it takes on some other layers of meaning.

First of all, Jesus says, “If your brother sins against you, go and show him his fault just between the two of you.” Notice the power distance there between the two parties in this conflict—there isn’t one. This is brother to brother. Not father to son, or son to father; not servant to master, or master to servant; not employer to boss or church member to pastor. Remember, Jesus is speaking this to his disciples, who were all brothers, roughly on the same plane as each other under Jesus.

Jesus continues by saying that if the brother will not listen and is not convinced of his fault, then the situation grows until he does—first with two or three other brothers, then with the whole church, and finally, if he will not listen, he is to be treated like a pagan or a tax collector. That means an outsider, a traitor, a nonbeliever. It might refer to church discipline or excommunication, but it certainly means he is treated as one who is not living out his faith and is therefore held to pagan standards, like a legal system or social shame, etc.

All of this is done ultimately to redeem both brothers from sin. But notice also, that all of this is done to protect the brother who has been sinned against, not the brother who sinned. And this is not a situation of mutual sin that he addresses; it is a clear cut, one-directional sin. Jesus asks the brother who has been wronged first to approach his brother on his own, but after that he is protected by witnesses, by the church, and then by the community at large.

Jesus drives home these points by reminding the disciples of the power they will hold: “whatever you bind on earth will be bound in heaven, and whatever you loose earth will be loosed in heaven.” Jesus tells the disciples, in effect, ‘If you package away a sin, it will stay hidden. But if you bring it into the light, it will be dealt with and released. Your judgments and actions will echo into eternity.’ He follows this scary responsibility with a statement of comfort: if they agree in their prayers, the Father will do what they ask. And when even two or three of them come together in Jesus’ name, he will be with them.

Church leaders have power and authority. But they are responsible to use it protectively. They have a weighty responsibility connected to their actions, but they will never have to make those judgments on their own.

After this discourse, Jesus closes his teachings on meek leadership with a powerful parable. Peter responds to the last teaching by very magnanimously suggesting that he might even be willing to forgive said brother (who sins against him) seven whole times, if Jesus were to ask him to. I can almost imagine Jesus’ chuckle as he answers, no, that Peter should in fact forgive seventy-seven times. I don’t know about poor fisherman Peter, but that’s a higher number than I can keep track of. I don’t have that many fingers, or that long of a memory. So Jesus means here: forgive more times than you can count.

As Jesus rounds out these teachings with this parable, we have learned that (1) meek leaders should protect and be gravely afraid of leading their little ones astray; (2) that they should consider each member of their flock just as important as themselves; (3) that they should protect the brother who has been sinned against by bringing sin into the light and not binding it away to hide it; and now (4), that leaders should show every mercy to those they lead, because they themselves have experienced greater mercy than they can ever measure or repay.

In this parable, Jesus describes a king settling accounts with his servants. One who owed an unassessable amount of money could not pay it back. It would take his whole life’s work and the work of his family to repay the debt. The servant begs for patience and makes a promise the King must know the man cannot keep—to pay back a life-debt. The king shows pity and completely cancels the debt. Not a penny owed.

This same servant then left and found a fellow servant to the king, who owed him a small amount. In his rage, the servant with the cancelled debt demands the other servant pay him, and begins to choke him! The debtor makes the same plea and promise—he asks for patience and promises to pay what he owes. Instead of cancelling this debt, or even agreeing to wait for his payment, the servant throws the man in prison until the debt is paid. The king calls the first servant back, tells him he is wicked, reinstates the man’s life-debt, and puts him in prison to be tortured until the money is paid. Jesus slams the parable home and says, “This is how my heavenly Father will treat each of you unless you forgive your brother from your heart.”

Jesus teaches his disciples, and us, that a meek leader should be forgiving and merciful. And in the process he shows us that God’s character (like the king in the story) is enflamed with rage when we mistreat our fellow servants, when we respond to their sins (debts against us) with rage and violence, accusation and harsh punishment. The king forgave the man’s life-debt in view of redemption. His mercy was to give the man an undeserved life of freedom when he showed repentance and a recognition of his sin (the debt he owed).

We are not to consider ourselves like the king in the story. We are the first servant, the unforgiving one. The only appropriate response to the Lord’s undeserved mercy to us is to show undeserved mercy to others. Any debt or sin others have committed us pales in comparison to what the Lord has already forgiven in our own life. Jesus isn’t asking us to cancel others’ debts and act as if they never sinned without reckoning up the damage they have done. He is merely asking of us patience. And a willing heart to forgive.

ANY LEADER who is abusive with his power and uses it to intimidate or control in order to take what he believes he is owed—like the first servant in the story—is NOT a meek leader. He angers God enough that he should undergo torture to pay a lifelong debt. Essentially, an abusive leader, or any person in God’s kingdom, deserves hell if he uses any power that he has over others harshly and without redemptive purpose. To put it in Jesus’ earlier words, it would be better for him to have a boulder hung around his neck and to be thrown into the sea to drown than to lead any of the little ones who follow Jesus astray.

These are harsh words. And they demonstrate Jesus’ meekness perfectly. He was a leader who protected the small, the young, the weak, the vulnerable, and held those in power to the highest accountability for how they use it over others.

Let me break up my own harsh words with a caveat. I, we, are all called to show the same grace and forgiveness to each other. It would be the height of hypocrisy for me to type on this keyboard and call leaders to account without recognizing that my own words on this screen should be held to the same standard, and without recognizing also that all of us have access to that same profound forgiveness and mercy the king showed. I owe the same forgiveness and mercy to any brother or sister who has wronged me. And if I extend that forgiveness, Jesus promises the same grace when my words and actions are weighed against me and found wanting.

So let me be clear when I say that I do feel pity, grace, and forgiveness for Christians who have not shown meekness in their leadership. Maybe they don’t sin in this way knowingly. And like I said before, the responsibility for this culture of leadership isn’t just on our leaders. It’s on us. We—I—have participated in faith communities that do not hold our leaders accountable. We—I—sit comfortably in systems that reward leaders for a near narcissistic confidence in their decisions and teachings. These systems take away our responsibility for our own spiritual growth and give it to teachers or people in power over us, and then pressure them to be productive in work they never should have been responsible for in the first place.

As a part of this grace, I recognize that our human nature leads us to fashion God in our own image. It’s why we make Jesus white in the West, why megachurch preachers see themselves in a Jesus who preaches to thousands, and why tough, abrasive leaders love to tell the story of Jesus turning tables. Our spiritual giftings reflect God’s character in us, as they are meant to. But it means that if we look only at ourselves and forget to value the multi-gifted church Body around us, we forget the other giftings that model other parts of Jesus’ character. I am a gentle soul. So “Jesus humble, meek and lowly” has always been the Jesus I have read into the gospels. Jesus with a whip, or Jesus publicly cursing religious leaders makes me deeply uncomfortable. Just like writing this blog post makes me deeply uncomfortable. But when we strive to reflect Jesus in every aspect of our lives, we will see growth in the areas of his character that we aren’t naturally prone to. When powerful leaders listen to the voices of the meek and lowly, they can learn to reflect Jesus in that way too.

Endnote

This ethic of meekness isn’t isolated to just Matthew chapter 18. When you’re paying attention, it pops up all over the Bible. Go and take a look for yourself. The book of Esther overflows with commentary on arrogant power abuse and the disastrous end it leads to. Esther and Mordecai depend on the Lord even in their positions of power—meekly—and through them the Lord saved his people. Psalm 37 holds the original verse Jesus quoted from in the sermon on the mount when he blesses the meek who will inherit the earth. Abigail meekly uses her shrewdness and influence to stay the hand of King David and keep him from sin. David himself is meant to be the archetype of Jesus, the Shepherd King who cares for his ‘flock’ as one from amongst them, not as an all-powerful ruler who uses the people under his care however he will.

But when Jesus comes onto the scene, we see this theme of meekness expand into the perfect expression these stories have been building up to the whole time. Throughout his ministry, Jesus’ teachings and character show us the paragon of meekness we should imitate. He IS the good shepherd, who fiercely fights for his sheep and would lay down his life for them. He welcomes little children, raises up widows from despair, comforts those who mourn, fills those who hunger and thirst with living water and bread of life, and delivers the kingdom to the poor in spirit. He shows us that to be the greatest in the kingdom and to inherit the earth, we must be meek as he is meek, and gentle and humble of heart. Jesus truly shows the very strength of the God of the universe tamed by gentleness. He balances the power and authority necessary to call out pharisees publicly with a tender care for the downtrodden. In my opinion, nowhere is this more striking than when he interacts with the woman caught in adultery in John 8.

The religious leaders rightfully call out a sin, but they abuse their power and shame her publicly for it. They behave just as the unmerciful servant does in Jesus’ parable we just discussed. Jesus places himself in the direct line of their ire to spare her from it, and reminds them of the debt they owe; slowly all of them realize that the woman isn’t the only one among them who has sinned. They drop the stones they would have thrown. And Jesus confronts the woman about her sin only after all of them have left. He does so gently, and privately. He does not minimize or side-step her sin, but he knows she is already aware of it and has suffered for it at the hands of power-abusing men. Without further shaming her in her vulnerable state, Jesus offers her the chance at a new life of walking in righteousness. He builds her up, and offers her redemption.

But I am afraid that just as Eve was deceived by the serpent’s cunning, your minds may somehow be led astray from your sincere and pure devotion to Christ. For if someone comes to you and preaches a Jesus other than the Jesus we preached, or if you receive a different spirit from the one you received, or a different gospel from the one you accepted, you put up with it easily enough. 2 Corinthians 11:3-4

Dear brothers and sisters, if your leaders have modeled Jesus’ leadership to you any other way, they have misrepresented him. In very real ways our spiritual leaders shape our view of God himself. They have a responsibility to model meekness along with their other leadership qualities, and to the extent that they fail to do so, they mar your understanding of the Lord whether they intend to or not. To any of you who have been harmed by spiritual abuse of this kind, I am deeply sorry. Any spiritual leader who consistently bullies or abuses power, and especially any spiritual leader who intimidates or manipulates in his or her bid for prestige and notoriety has not shown you the meek leadership of Christ. If they refuse correction like the brother in Jesus’ teachings, they are to be held responsible and accountable for their actions But we are accountable too, for leaving this type of leadership unchallenged in our ranks for so long.

Other, smarter, more well-informed people have written much better and more eloquently about this. These themes run through some strains of liberation theology, Black theology, and feminist theology. Diane Langberg, Chuck DeGroat, Rachael Clinton Chen, and others have made abusive church leadership and the devastation of spiritual abuse their field of study, and their resources are invaluable. The Rise and Fall of Mars Hill podcast by Christianity Today is also a good introduction to open our eyes to the abuses of church leadership.

Other people have said these things better, but perhaps I’m just the person in your circle sharing these ideas with a familiar voice. Regardless of how you hear about meekness and spiritual abuse, “By the meekness and gentleness of Christ, I appeal to you:” don’t let it fall on deaf ears. We have a church culture to change. Let’s get to work.

My love for birds comes from my dad. He has always been one to seek out wonder in the world around him, so it makes sense that he took a completely unnecessary ornithology class in college. I have early memories of sitting in a car in parking lots with him, partway through some errand or another. In the middle of an oil-stained landscape of tarred gravel, sketchy yellow lines, and exhaust fumes, he would point out the birds who found themselves at home in it.

He taught us to know their shapes and colorings, and slowly I learned which birds were more likely to pick up stale McDonald’s French fries with no fear of the nearby humans, which birds perched on the stacked-up shopping carts and bobbed their tails at rest, and which birds preferred to sit atop the street lights only to swoop down once the coast was absolutely clear. We played a treasure-hunting game, looking for birds and calling out their names before another sibling could beat us to it: Boat-tailed grackle! Brown-headed cowbird! Crow! Sparrow!

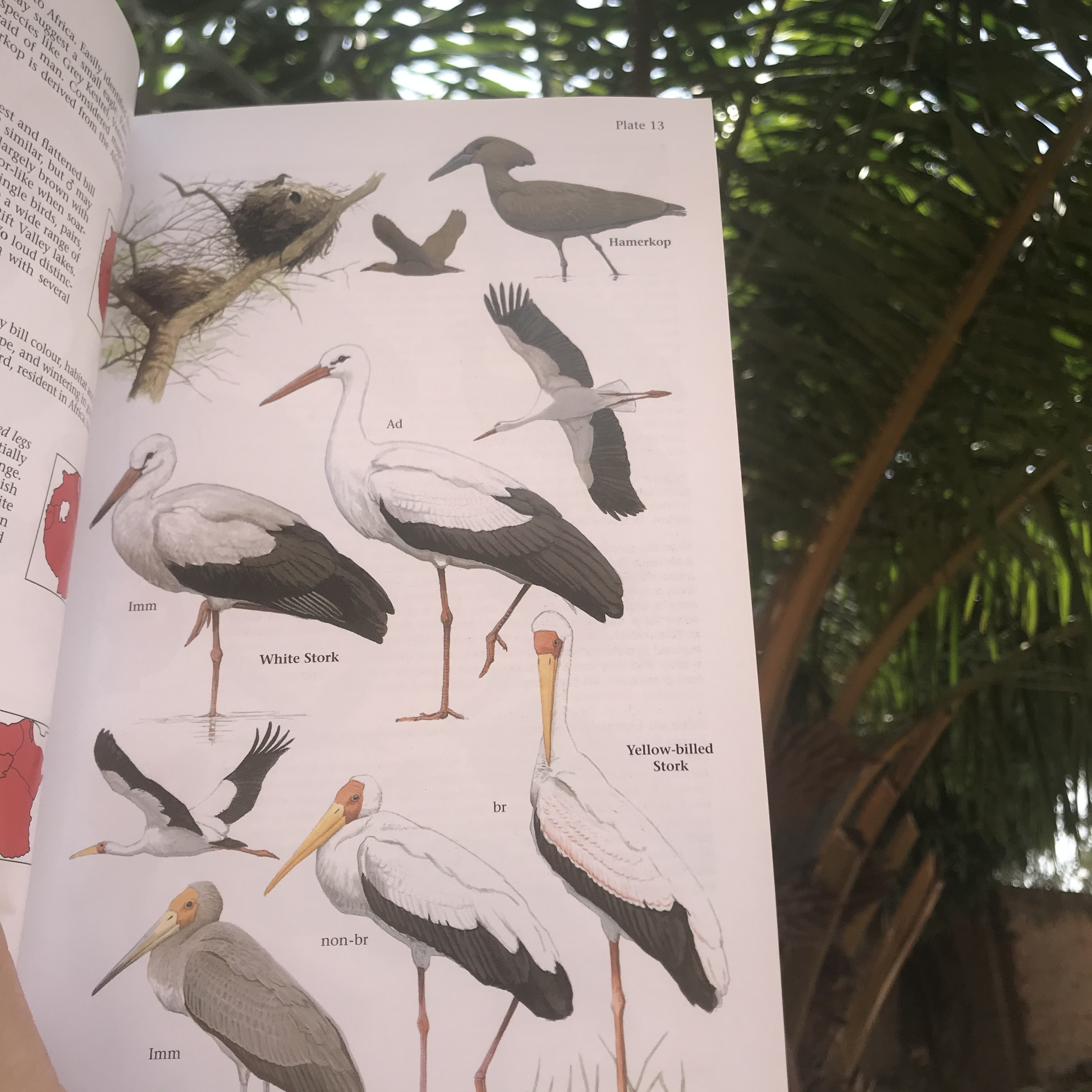

Dad passed on his love for nature, as well as the “Birds of East Africa” guidebook which sits easily accessible in my living room. Its dog-eared pages and starred descriptions show how often I try to identify a new bird, or show off one of the rarer ones I have happened to see. We also played the same identification game with trees, so I often find myself googling bark textures or leaf patterns to identify local trees. Or without provocation I’ll find myself asking no one in particular if African eucalyptus trees are different from the ones koalas eat in Australia.

I first noticed this same wonder and curiosity in myself for trees and birds (and insects and animals) when I met it in Wendell Berry’s writings. If you haven’t read any of his writings (or even if you have!), do yourself a favor and go read some by a stream or under a tree. He often writes on themes connecting community to landscape. Knowing the growing things of a place can ground you there—give you a sense of place, and a feel for the roots beneath your feet. I feel I know a place where I live if I can name its trees and crops, and if I know which of its birds are common and which rare ones deserve to be treasured.

I’m an expat. I live now on different dirt than I was raised on. The dust on my feet at the end of the day was made from centuries of birth, life, and death foreign to my experience. In many ways I don’t belong to this place and it doesn’t belong to me. My life here has shallow roots like the weeds that spring up almost overnight during rainy season and are easily swept away, withered and brittle, by the dust devils of dry season. There isn’t always much stable to hold onto in this expat life, so I cling to fragile community that comes and goes with the seasons. I get overly-attached to pets committed to me as long as I’m committed to be here, if for no other reason than for their needs of food and nurturing.

I dig deep, send out roots, drink in the water of this place, and wear its dust. And in the end, maybe that is why the creatures and growing things of a place bring me so much comfort; they root me to the land. They were raised on ages of instinct and adaptation shaped by the landscape. They take in the recycled water of generations. They grow on a bed of earth built piece by piece from the fallen leaves and withered grass and trampled dung of centuries. The life that grows and flies and crawls in this place has a much longer memory than I.

Recently I learned about one of these creatures that now has a special place my heart. My scattered roots had me reading up and preparing to celebrate Baba Marta day, a Bulgarian holiday to welcome spring. I missed an historic snow in Oklahoma, and the temperature gap between that winter blizzard and my dry season dust storm had me longing for a place with spring, with tender flowers peeking fresh blooms through the snow, and the smell of linden flowers and paths carpeted with fallen redbud blossoms.

As I read again about Baba Marta day and debated whether to make martenitsa to tie or medinki to eat, I read about the storks. Bulgarians wear a martenitsa bracelet or pin beginning on Baba Marta day, and they should take it off and tie it to a tree the first time they see flowering plants or a migrating stork returned from its wanderings. I remember seeing these storks frequently in Bulgaria, and even while the birds were gone for the winter, you could see their impossibly wide nests still adorning buildings or slender telephone poles anywhere in the country.

Further research showed that the same storks who travel to Bulgaria in March migrate south to spend Europe’s cold winter in Africa. Many even spend those months here, in Uganda. These migratory birds stuck a chord with me. I, who sometimes feel as if I’m always in a slow-going migratory pattern from one place to another, building my nest perched precariously in some of the most unlikely places, leaving for warmer skies when the wind changes, living without much footprint, moving back and forth making a life of travel and in-betweens.

I have a Gypsy wagon wheel tattooed on my body to remind me that I sojourn through this world, refusing to settle until I find the better, heavenly country that my heart desires. Jesus himself said that foxes have dens and birds have nests, but he had no place to lay his head. He trained his disciples to set out taking with them a walking stick, the clothes on their back, and a hope of finding a welcoming home to kick off their sandals and wash their feet.

But that picture of a wanderer isn’t the only one that comes from Hebrews 11. Our faith drives us onward to sojourn until we reach heaven. But that doesn’t mean our hearts won’t feel unsettled and long for home the whole time. Even as we recognize our fragility and homelessness, we stay in tents and make our temporary home as best we can. We look forward with assurance of our hope to a city—with foundations: roots into our earth that will be changed, but will very much still be here once heaven arrives on it.

The one who labors to dig those foundations and set the stone into the earth is our Lord himself, designing, preparing, and building a home for us. If we don’t carry that longing around burning like an ember in our hearts, we’ve missed the point entirely of our sojourning. We yearn. We long for our heavenly country with all of our heart, and as we wander and long, our God is not ashamed to be called by our name. He goes ahead to prepare a place for us.

My longing to make a home with roots is not wrong. Nor is my ease in picking up and traveling. Both longings are rooted in a need to reach my eternal home someday. And a believer who lives in one town their whole lives has just as much of a picture and a fierce longing for that heavenly home as does a believer who never lived anywhere longer than 3 years at a time.

Our Lord directed our gaze to the birds of the air, who do not plant or harvest, or store away things for themselves. If he can feed them and sustain their lives, how much more will he keep us? If a stork can be as easily at home perched on a lone telephone pole in a gypsy slum as in the grasslands of sub-Saharan Africa, it is only because the Lord creates in it a desire to make those places home and provides for its needs. If a stork can belong to both words, so can I. And if the Lord can clothe and shelter birds in their migrations between worlds, so can he for me.

“White Stork is the classic stork nesting on buildings in Europe, and wintering in grasslands throughout sub-Saharan Africa.”

“Princeton Field Guides: Birds of East Africa,” Terry Stevenson and John Fanshawe, Princeton Press, 2002, 26-27.

I have a wagon wheel tattooed on my leg. It’s a pretty permanent reminder of impermanence. I like to take pictures of it whenever I travel somewhere new, to keep a chronicle of all the places I’ve ‘parked my wagon wheels.’ But its meaning is so much deeper than that.

A few years ago I lived and worked with the Roma people in Bulgaria. Known and stereotyped for their nomadic, ‘caravan’ lifestyle, this community taught me a lot about transience. I learned what it is to make a home wherever you are, to not depend so much on a place and its things as on your people. I experienced life embraced by a ‘clan’ and accepted as family even though the difference in my culture and skin tone were as obvious as night and day. I felt all the hard goodbyes without a promised ‘see you next time,’ and all the joyful reunions and relationships that picked up right where they left off, no matter how much time had elapsed.

My ‘gypsy’ years taught me a lot about expat life. I live in a country that doesn’t match my passport, so I’m an expatriate, and I experience all the joys and sorrows, trials and triumphs attendant to this special lifestyle.

Being an expat means I know things can turn on a dime. Life can change drastically in a matter of hours or days, and you have to roll with the punches. It means I say a lot of goodbyes. It means I have built lots of rich relationships. It means I have friends in lots of different corners of the world. It means sometimes the people closest to my heart actually live the farthest away from me. It means having a go-bag in my closet. It means trying to monitor a sometimes overwhelmingly foreign culture for a few signs of ‘different’ that mean something isn’t right. It means being misunderstood and misunderstanding. It means stuttering along in the language of a friend. It sometimes means being utterly, nakedly, vulnerable and dependent upon the kindness of strangers and new friends. It means I build family fast and bond deeply but sometimes I hate myself for it because goodbyes are awful. It means opening my home to strangers because I know what it means to be welcomed in as one myself. It means a rollercoaster of emotions and changes. It makes for a wild ride.

This worldwide pandemic going on right now has really made the impermanence of expat life stand out harshly. In the past week alone I’ve felt the border crossings lock tight shut around me. I’ve helped friends, neighbors, coworkers pack to leave the country at the drop of a hat. After much anguish and many changed plans, they got out of the country on one of the last possible flights. I’ve stocked up my house in case social upheaval keeps me indoors. Unnatural crowd sizes made my skin prickle. I’ve fielded texts and calls from friends and acquaintances leaving that I didn’t even get to say goodbye to. I’ve kept a wary eye on emails from the embassy. I’ve played ridiculous games in the market shopping with friends to create some sense of lightness and normalcy. I’ve munched on a mendazi in town while counting heads to make sure I was spatially aware of my people… just in case. I’ve cried hard and laughed hard. I’ve stress baked until it seems like every surface in my house is dusted with flour. I’ve belted out my emotions singing along with “I’m just too good at goodbyes” and “all by myself” and “big wheel keep on turnin'” along with plenty of hymns and worship music as well.

This expat life can be an extra source of stress at times when everywhere in the world has more than enough stress to go around. But the flip side of that coin is that this life has taught me and better prepared me for such a time as this.

Coronavirus didn’t do much to remind me of the impermanence of life and home and relationships. I carry that thought always at the back of my mind and tattooed on my leg. I didn’t need a worldwide pandemic to firmly plant in my heart the truth that our home in this world is never promised, but that we deeply long for a permanent one with our Creator. In times of trouble my mind and heart already ask with Moses, “teach us to number our days, that we may gain a heart of wisdom.” My life carries a base level of urgency already because I know not to take the days for granted and to make the most of relationships and opportunities here and now. As volatile as life is right now, and as much as my whole world changes sometimes by the hour, I have the immovable hope and assurance that my real home doesn’t change. My heavenly home waits for me just the same, and the parts of my life given to build up that kingdom will not go to waste—no matter what happens in the world around me.

Another huge comfort is knowing that God is not surprised by times such as these. No matter where you are trapped or stranded or locked down, God is there with you. When God appeared to Ezekiel and the Hebrew exiles, he chose to show himself as a wheel. Wherever we may be, and however far from home and family it feels, God reminds us that he is an ever-present, traveling God. He sees us. He knows us. And without moving himself, he is with us wherever we go. He was there before us and he’ll be there behind us. And that is a great comfort to this expat heart.

As I looked at the living creatures, I saw a wheel on the ground beside each creature with its four faces. This was the appearance and structure of the wheels: They sparkled like topaz, and all four looked alike. Each appeared to be made like a wheel intersecting a wheel. As they moved, they would go in any one of the four directions the creatures faced; the wheels did not change direction as the creatures went. Their rims were high and awesome, and all four rims were full of eyes all around.

When the living creatures moved, the wheels beside them moved; and when the living creatures rose from the ground, the wheels also rose. Wherever the spirit would go, they would go, and the wheels would rise along with them, because the spirit of the living creatures was in the wheels. When the creatures moved, they also moved; when the creatures stood still, they also stood still; and when the creatures rose from the ground, the wheels rose along with them, because the spirit of the living creatures was in the wheels.

Have you ever watched the movie Ratatouille? It’s a fun kids’ movie about a rat who cooks fancy French cuisine. I love how the film shows how important food is in our cultural identities, our families, building new relationships, and feeding old ones. At the movie’s climax, the heartless food critic tastes a dish that takes him back to his childhood. In the briefest of flashbacks, he pictures his mother, her kitchen, and the food she cooked to lift his spirits. The simple dish brought him joy and memories of togetherness.

I had a Ratatouille flashback of my own this week. Most of my team was gathered together out at a remote ministry site, and in the evenings we shared our meals together. I was in my happy place, in the kitchen cooking for over 20 people, covered in flour, and listening to conversations and stories centered around the dining table as we all waited for the meal to be prepared.

A friend helping me in the kitchen commented about the pie crusts, fresh out of the oven and waiting for quiche filling. The buttery smell wafting through the kitchen took me back to my preteen years at GA camp.

When I was a girl, Oklahoma had a wonderful Girls in Action camp, called Nunny Cha-Ha, where I went every summer to spend time growing with the Lord and learning all about missions. Lots of shenanigans were carried out there, and lots of fun memories made, but it was on one of those splintery wooden tabernacle benches that I first understood the Lord’s call to missions on my life.

One summer at camp, I was in a cooking class elective. I probably chose it just so I could ‘go behind the curtain’ to the secret world of the industrial-sized kitchen. I was old enough to have some angst about gender roles: “Are they teaching us to cook and bake just because we’re girls? That doesn’t seem fair! What does that have to do with missions?”

A staffer—whose name I can’t remember, and who probably knows nothing of the impact she had on me—taught us awkward girls a lesson that has stuck with me. She explained how food is an important part of culture, and that sharing your cultural food with someone can build friendships. Good food can create opportunities to share about your faith in Jesus. She told us how she would bake with her international friends, and how sharing food can be a real, physical way to show God’s love to someone.

We made simple cherry pies that day, with just a few ingredients and cans of pie filling. Of course I loved eating my tiny pie, but even sweeter and longer-lived was the realization that I enjoyed baking to share with others. That was when my love of time in the kitchen began.

I saved that raggedy piece of paper with a pie crust recipe for years, until I re-wrote it on a recipe card that has traveled all around the world with me. I have the recipe memorized now, and the recipe card is so stained and crumpled and oil-soaked that it’s barely legible.

The aroma of buttery pie crust brought all those memories back, along with some fresh understandings of how the Lord had stewarded my life and experiences. As I stood in that kitchen, covered in flour, in the middle of the African bush, cooking quiches to feed a couple dozen people, I shared my story with a friend.

The Lord used a simple pie crust at a girls’ mission camp to reveal my love for baking. He showed me he could use all my gifts and talents on the mission field, even the simple, humble ones. Today that pie crust has been to many a church social and potluck. It’s been served to local and international friends wherever I’ve lived in the States. It’s been the humble base for birthday pies and apple dumplings. It’s been delivered to new neighbors to start relationships. It held a Thanksgiving pumpkin pie in Bulgaria. A group of Sudanese refugee ladies and a Kenyan woman living in Uganda use it to make apple pies. They sell the pies to help support their families and feed hungry guests at our co-op coffee shop. And just this week in the middle of the bush it fed hungry families after a long day of ministry.

That crust wasn’t just a base for quiche or pie; it’s been a base for conversations, for friendships, for memories, for service, and for love.

It’s one well-traveled pie crust, and a testament to the Lord’s sovereignty. He can take small things like a pie, or an awkward tween at GA camp, and use them all over the world for his glory.

Mix 2 cups of flour with 1 tsp of salt.

Cut in ¾ cup shortening, margarine, or butter.

Mix in 3-5 TBS of cold water.

Roll out or shape the pie crust into the bottom of an 8 or 9” pie pan.

Pre-bake crust for 5-10 minutes at 400 F.