“A thrill of hope, the weary world rejoices”

That song lyric has played on a loop in my mind for the past week. Our world certainly feels weary this year. Many of us put up the Christmas decorations early, started in on Christmas music before we normally would, and still we ache for that special “Christmas” feeling to redeem and round off what has been one of our least favorite years in recent memory.

In our weariness, it can be hard to feel hopeful. Maybe Christmas doesn’t feel the same, or maybe you’re just too worn out this year to put in the effort. I love Christmas more than most, but this year I showed extra restraint and waited to decorate until after Thanksgiving. I wanted Christmas to be special, reserved for a short time period, refreshing. But it wasn’t.

I felt heavy exhaustion in my body as I raised my arms to hang an ornament. I caught myself wanting to do anything else besides decorate, which usually sends me into giggles because of the wonder and giddy excitement I feel. As I played O Come, O Come Emmanuel on the piano, the music abruptly stopped a I reached the chorus. The words caught in my throat and I physically couldn’t continue. The transition from a melancholy minor to “rejoice, rejoice!” was too quick and hypocritical for me. Rejoicing feels far away from my thoughts, and my heart is bowed under burdens, not lifted up with hope.

But I’m learning this year that celebrating Christmas is a discipline. We should keep in the habit of practicing it whether we feel festive or not. In one of my favorite Christmas stories, the redemption comes at the end when we learn that, “It was always said of [Scrooge], that he knew how to keep Christmas well, if any man alive possessed the knowledge. May that truly be said of us, and all of us!”

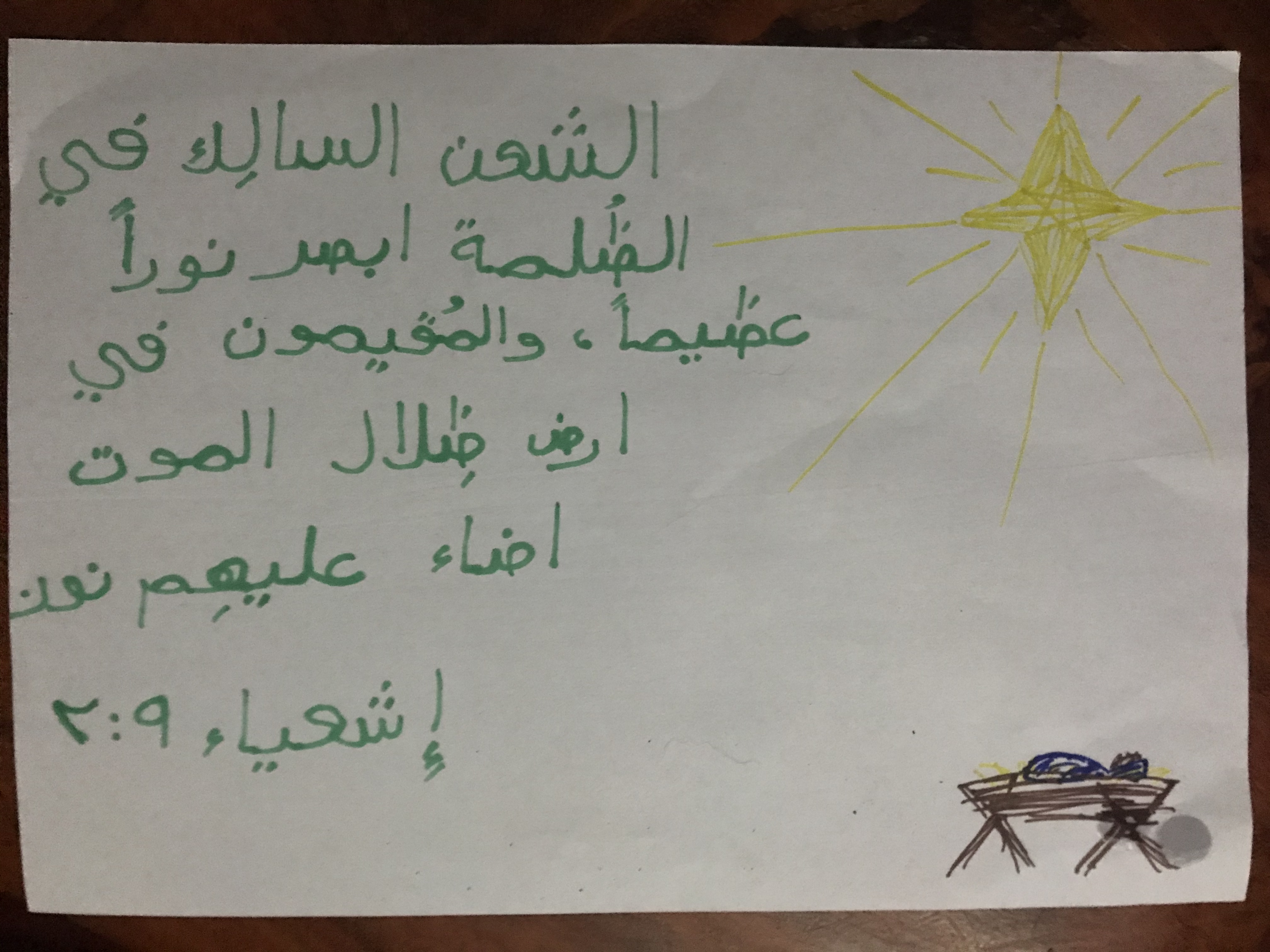

Keeping Christmas—cultivating hope—is a spiritual discipline. Christmas is for celebrating in the bleak midwinter. It’s for recognizing a light shining in the darkness that darkness cannot overcome. It’s a time when we remember that people walking in darkness have seen a great light, and that light has dawned on those living in a land of deep darkness. Christmas is the perfect time to celebrate hope in the midst of weariness, and joy underneath heavy burdens. It’s a time to celebrate awe strong enough to defeat cynicism, and wonder fresh enough to see miracles in an unbelieving world.

But these attitudes of worship—hope, awe, wonder, joy—they don’t just happen on their own. I have deeply loved Christmas since I was small, and that was in large part because I was fed Christmas cheer from every side. Many of my favorite memories are of these feelings. I vividly recall watching the stars at night as my family traveled to see relatives. Sometimes I watched in wonder for the silhouette of a sleigh to block out patches of stars on its way to deliver gifts. But I looked up and wondered also about what the star over Jesus’ birth looked like. I felt joy at opening gifts chosen by loved ones with great care, or at watching them open gifts I has lovingly chosen for them. I’ve spent hours of my life gazing in awe at the lights on Christmas trees, even as an adult. My jaw comically hangs open every time I breathlessly look at the fresh sparkle of snow under moonlight. And I learned of hope at a young age too, every year as we took down the Christmas decorations and I looked forward with trusting anticipation to next year when they would come out again.

As a child, these feelings surrounded me. Whether they were directed in worship or in childish fun, the “feeling of Christmas” was in the air and the ether. I absorbed it through the radio Christmas music, the tv programs, church events, holiday parties, and my parents’ faithful practice of advent. But as I grew up, the weight of the world grew heavier. “Christmas in the air” wasn’t enough, and I had to practice advent for myself, disciplining myself to remember hope in darkness, and to tend seeds of joy in the midst of suffering. Even now, this Christmas in Africa, I’m more likely to see a palm tree than an evergreen. And I can’t fall asleep on the couch to the soft glow of Christmas lights, because the mosquitos make it unbearable to be anywhere but under a net. Christmas cheer takes extra work some years.

A dear friend recently visited and I felt a thrill of hope in my for the first time this season. she carries a new baby inside her, and it brought tears to my eyes to feel that new life pressing between us as we hugged for the first time in too long. And later when I sat beside her, my hand on her stomach, waiting to feel the movement of life there, tears cam instantly to my eyes and my heart leapt.

A thrill of hope.

I remembered the story of Elizabeth, and how her baby leapt in her womb at the voice of Mother Mary. I remembered that small, fragile life can come in the humblest of circumstances and brings with it awe, joy, wonder, and hope.

It takes practice and discipline to train our hearts and minds to seek out these jolts of hope. It is hard work to recognize these moments of worship and let them wash over us to renew our mind and refocus our attention.

The liturgical calendar our mothers and fathers in the faith practiced is full of wisdom. It gives us patterns and rhythms to set aside times of the year for turning our mind to consider Jesus’ earthly life. These calendar year celebrations of Christmas or Easter were meant to give us discipline and practice. They give us the opportunity every year to wait expectantly on the birth and return of Jesus as we look behind to remember and look forward in hope.

So celebrate advent however you need to this year; set aside time or activities to remind yourself of the hope, awe, wonder, and joy the birth of Jesus brings even today. Put up your Christmas tree and turn on the Christmas playlist. Make cookies with a child who will find joy in the sugary mess of icing dripped across the counters. Bury your face in an evergreen tree and remember that the resinous scent means life continues through bleak midwinter. Look at the cold stars and find awe there that our God is Emmanuel, who came down once to be with us. Gaze into a crackling fire and feel the warm hope that a dark night of the soul will not last forever. Hold a candle in the darkness and marvel how a fragile, flickering flame can powerfully push back the darkness. Seek out the thrill of new life. Train yourself to find these worshipful moments. Thank the Lord of the gift of his son and the hope that He brings.

Emmanuel,

May we find room in our thoughts for you

As we celebrate your birth long ago when there was no room.

We desire to give you special awed Christmas worship

Even as you give us hope to hold out against the darkness.

Revive our weary souls with wonder at the thrill of new life.

As we wait expectantly for you to come again give us sweet joy

For the sight it will be when you return in kingly robes instead of manger hay.

Train our hearts on yourself, the object of our great wonder.

Give us practice in turning our thoughts toward awe at your goodness.