Liminal: an adjective to describe a transitional stage or something on a boundary ‘Liminal’ has long been a favorite word of mine. It always reminds me of the colored bands … Continue reading

Liminal: an adjective to describe a transitional stage or something on a boundary ‘Liminal’ has long been a favorite word of mine. It always reminds me of the colored bands … Continue reading

My love for birds comes from my dad. He has always been one to seek out wonder in the world around him, so it makes sense that he took a completely unnecessary ornithology class in college. I have early memories of sitting in a car in parking lots with him, partway through some errand or another. In the middle of an oil-stained landscape of tarred gravel, sketchy yellow lines, and exhaust fumes, he would point out the birds who found themselves at home in it.

He taught us to know their shapes and colorings, and slowly I learned which birds were more likely to pick up stale McDonald’s French fries with no fear of the nearby humans, which birds perched on the stacked-up shopping carts and bobbed their tails at rest, and which birds preferred to sit atop the street lights only to swoop down once the coast was absolutely clear. We played a treasure-hunting game, looking for birds and calling out their names before another sibling could beat us to it: Boat-tailed grackle! Brown-headed cowbird! Crow! Sparrow!

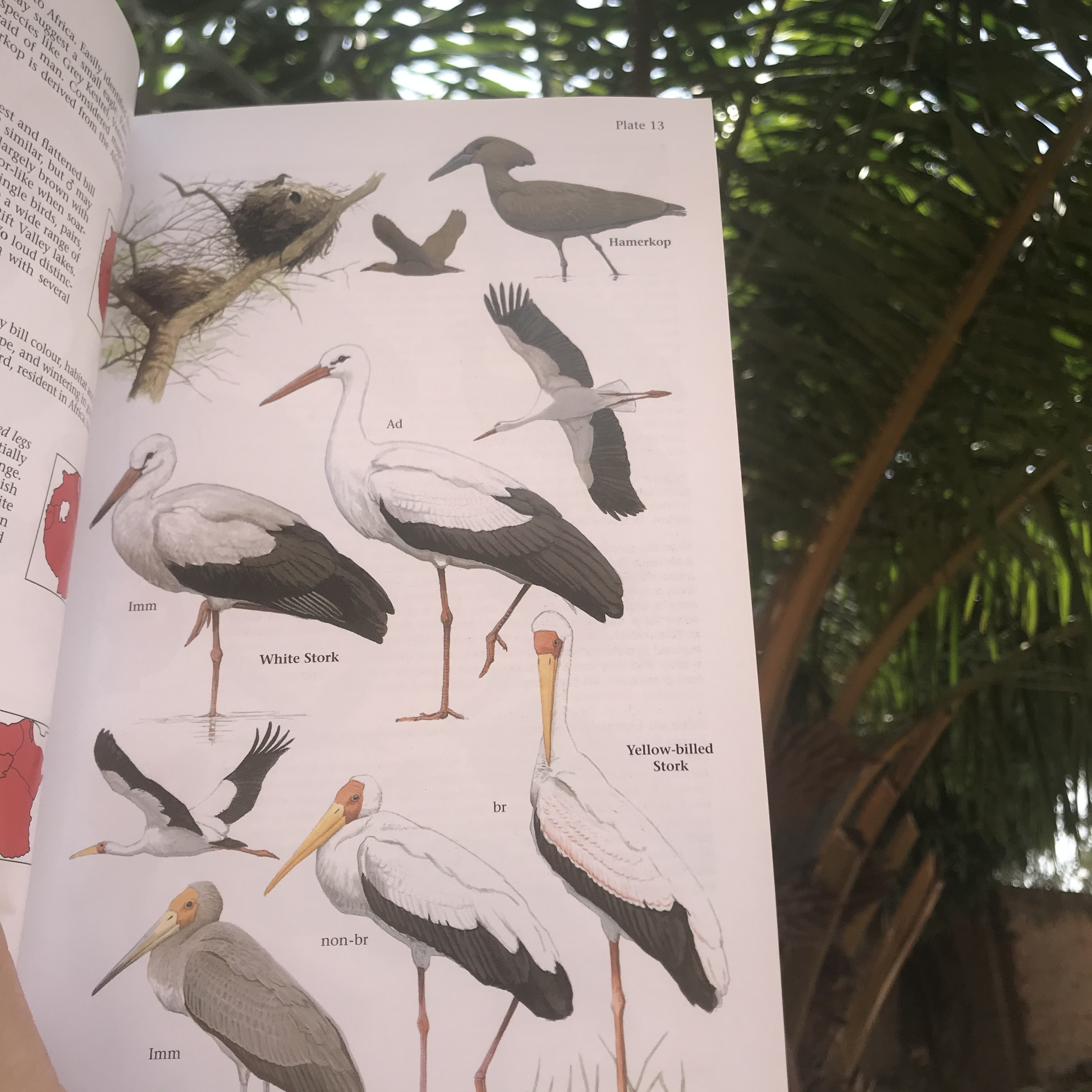

Dad passed on his love for nature, as well as the “Birds of East Africa” guidebook which sits easily accessible in my living room. Its dog-eared pages and starred descriptions show how often I try to identify a new bird, or show off one of the rarer ones I have happened to see. We also played the same identification game with trees, so I often find myself googling bark textures or leaf patterns to identify local trees. Or without provocation I’ll find myself asking no one in particular if African eucalyptus trees are different from the ones koalas eat in Australia.

I first noticed this same wonder and curiosity in myself for trees and birds (and insects and animals) when I met it in Wendell Berry’s writings. If you haven’t read any of his writings (or even if you have!), do yourself a favor and go read some by a stream or under a tree. He often writes on themes connecting community to landscape. Knowing the growing things of a place can ground you there—give you a sense of place, and a feel for the roots beneath your feet. I feel I know a place where I live if I can name its trees and crops, and if I know which of its birds are common and which rare ones deserve to be treasured.

I’m an expat. I live now on different dirt than I was raised on. The dust on my feet at the end of the day was made from centuries of birth, life, and death foreign to my experience. In many ways I don’t belong to this place and it doesn’t belong to me. My life here has shallow roots like the weeds that spring up almost overnight during rainy season and are easily swept away, withered and brittle, by the dust devils of dry season. There isn’t always much stable to hold onto in this expat life, so I cling to fragile community that comes and goes with the seasons. I get overly-attached to pets committed to me as long as I’m committed to be here, if for no other reason than for their needs of food and nurturing.

I dig deep, send out roots, drink in the water of this place, and wear its dust. And in the end, maybe that is why the creatures and growing things of a place bring me so much comfort; they root me to the land. They were raised on ages of instinct and adaptation shaped by the landscape. They take in the recycled water of generations. They grow on a bed of earth built piece by piece from the fallen leaves and withered grass and trampled dung of centuries. The life that grows and flies and crawls in this place has a much longer memory than I.

Recently I learned about one of these creatures that now has a special place my heart. My scattered roots had me reading up and preparing to celebrate Baba Marta day, a Bulgarian holiday to welcome spring. I missed an historic snow in Oklahoma, and the temperature gap between that winter blizzard and my dry season dust storm had me longing for a place with spring, with tender flowers peeking fresh blooms through the snow, and the smell of linden flowers and paths carpeted with fallen redbud blossoms.

As I read again about Baba Marta day and debated whether to make martenitsa to tie or medinki to eat, I read about the storks. Bulgarians wear a martenitsa bracelet or pin beginning on Baba Marta day, and they should take it off and tie it to a tree the first time they see flowering plants or a migrating stork returned from its wanderings. I remember seeing these storks frequently in Bulgaria, and even while the birds were gone for the winter, you could see their impossibly wide nests still adorning buildings or slender telephone poles anywhere in the country.

Further research showed that the same storks who travel to Bulgaria in March migrate south to spend Europe’s cold winter in Africa. Many even spend those months here, in Uganda. These migratory birds stuck a chord with me. I, who sometimes feel as if I’m always in a slow-going migratory pattern from one place to another, building my nest perched precariously in some of the most unlikely places, leaving for warmer skies when the wind changes, living without much footprint, moving back and forth making a life of travel and in-betweens.

I have a Gypsy wagon wheel tattooed on my body to remind me that I sojourn through this world, refusing to settle until I find the better, heavenly country that my heart desires. Jesus himself said that foxes have dens and birds have nests, but he had no place to lay his head. He trained his disciples to set out taking with them a walking stick, the clothes on their back, and a hope of finding a welcoming home to kick off their sandals and wash their feet.

But that picture of a wanderer isn’t the only one that comes from Hebrews 11. Our faith drives us onward to sojourn until we reach heaven. But that doesn’t mean our hearts won’t feel unsettled and long for home the whole time. Even as we recognize our fragility and homelessness, we stay in tents and make our temporary home as best we can. We look forward with assurance of our hope to a city—with foundations: roots into our earth that will be changed, but will very much still be here once heaven arrives on it.

The one who labors to dig those foundations and set the stone into the earth is our Lord himself, designing, preparing, and building a home for us. If we don’t carry that longing around burning like an ember in our hearts, we’ve missed the point entirely of our sojourning. We yearn. We long for our heavenly country with all of our heart, and as we wander and long, our God is not ashamed to be called by our name. He goes ahead to prepare a place for us.

My longing to make a home with roots is not wrong. Nor is my ease in picking up and traveling. Both longings are rooted in a need to reach my eternal home someday. And a believer who lives in one town their whole lives has just as much of a picture and a fierce longing for that heavenly home as does a believer who never lived anywhere longer than 3 years at a time.

Our Lord directed our gaze to the birds of the air, who do not plant or harvest, or store away things for themselves. If he can feed them and sustain their lives, how much more will he keep us? If a stork can be as easily at home perched on a lone telephone pole in a gypsy slum as in the grasslands of sub-Saharan Africa, it is only because the Lord creates in it a desire to make those places home and provides for its needs. If a stork can belong to both words, so can I. And if the Lord can clothe and shelter birds in their migrations between worlds, so can he for me.

“White Stork is the classic stork nesting on buildings in Europe, and wintering in grasslands throughout sub-Saharan Africa.”

“Princeton Field Guides: Birds of East Africa,” Terry Stevenson and John Fanshawe, Princeton Press, 2002, 26-27.

I have a wagon wheel tattooed on my leg. It’s a pretty permanent reminder of impermanence. I like to take pictures of it whenever I travel somewhere new, to keep a chronicle of all the places I’ve ‘parked my wagon wheels.’ But its meaning is so much deeper than that.

A few years ago I lived and worked with the Roma people in Bulgaria. Known and stereotyped for their nomadic, ‘caravan’ lifestyle, this community taught me a lot about transience. I learned what it is to make a home wherever you are, to not depend so much on a place and its things as on your people. I experienced life embraced by a ‘clan’ and accepted as family even though the difference in my culture and skin tone were as obvious as night and day. I felt all the hard goodbyes without a promised ‘see you next time,’ and all the joyful reunions and relationships that picked up right where they left off, no matter how much time had elapsed.

My ‘gypsy’ years taught me a lot about expat life. I live in a country that doesn’t match my passport, so I’m an expatriate, and I experience all the joys and sorrows, trials and triumphs attendant to this special lifestyle.

Being an expat means I know things can turn on a dime. Life can change drastically in a matter of hours or days, and you have to roll with the punches. It means I say a lot of goodbyes. It means I have built lots of rich relationships. It means I have friends in lots of different corners of the world. It means sometimes the people closest to my heart actually live the farthest away from me. It means having a go-bag in my closet. It means trying to monitor a sometimes overwhelmingly foreign culture for a few signs of ‘different’ that mean something isn’t right. It means being misunderstood and misunderstanding. It means stuttering along in the language of a friend. It sometimes means being utterly, nakedly, vulnerable and dependent upon the kindness of strangers and new friends. It means I build family fast and bond deeply but sometimes I hate myself for it because goodbyes are awful. It means opening my home to strangers because I know what it means to be welcomed in as one myself. It means a rollercoaster of emotions and changes. It makes for a wild ride.

This worldwide pandemic going on right now has really made the impermanence of expat life stand out harshly. In the past week alone I’ve felt the border crossings lock tight shut around me. I’ve helped friends, neighbors, coworkers pack to leave the country at the drop of a hat. After much anguish and many changed plans, they got out of the country on one of the last possible flights. I’ve stocked up my house in case social upheaval keeps me indoors. Unnatural crowd sizes made my skin prickle. I’ve fielded texts and calls from friends and acquaintances leaving that I didn’t even get to say goodbye to. I’ve kept a wary eye on emails from the embassy. I’ve played ridiculous games in the market shopping with friends to create some sense of lightness and normalcy. I’ve munched on a mendazi in town while counting heads to make sure I was spatially aware of my people… just in case. I’ve cried hard and laughed hard. I’ve stress baked until it seems like every surface in my house is dusted with flour. I’ve belted out my emotions singing along with “I’m just too good at goodbyes” and “all by myself” and “big wheel keep on turnin'” along with plenty of hymns and worship music as well.

This expat life can be an extra source of stress at times when everywhere in the world has more than enough stress to go around. But the flip side of that coin is that this life has taught me and better prepared me for such a time as this.

Coronavirus didn’t do much to remind me of the impermanence of life and home and relationships. I carry that thought always at the back of my mind and tattooed on my leg. I didn’t need a worldwide pandemic to firmly plant in my heart the truth that our home in this world is never promised, but that we deeply long for a permanent one with our Creator. In times of trouble my mind and heart already ask with Moses, “teach us to number our days, that we may gain a heart of wisdom.” My life carries a base level of urgency already because I know not to take the days for granted and to make the most of relationships and opportunities here and now. As volatile as life is right now, and as much as my whole world changes sometimes by the hour, I have the immovable hope and assurance that my real home doesn’t change. My heavenly home waits for me just the same, and the parts of my life given to build up that kingdom will not go to waste—no matter what happens in the world around me.

Another huge comfort is knowing that God is not surprised by times such as these. No matter where you are trapped or stranded or locked down, God is there with you. When God appeared to Ezekiel and the Hebrew exiles, he chose to show himself as a wheel. Wherever we may be, and however far from home and family it feels, God reminds us that he is an ever-present, traveling God. He sees us. He knows us. And without moving himself, he is with us wherever we go. He was there before us and he’ll be there behind us. And that is a great comfort to this expat heart.

As I looked at the living creatures, I saw a wheel on the ground beside each creature with its four faces. This was the appearance and structure of the wheels: They sparkled like topaz, and all four looked alike. Each appeared to be made like a wheel intersecting a wheel. As they moved, they would go in any one of the four directions the creatures faced; the wheels did not change direction as the creatures went. Their rims were high and awesome, and all four rims were full of eyes all around.

When the living creatures moved, the wheels beside them moved; and when the living creatures rose from the ground, the wheels also rose. Wherever the spirit would go, they would go, and the wheels would rise along with them, because the spirit of the living creatures was in the wheels. When the creatures moved, they also moved; when the creatures stood still, they also stood still; and when the creatures rose from the ground, the wheels rose along with them, because the spirit of the living creatures was in the wheels.

It’s been 6 months. Six looooong months, of adjusting to heat and new diseases and inconsistent electricity. But it’s also been six short months, of learning a beautiful language, building relationships, making new friends, loving the sunshine and the rain and the growing things, and making a home. I could give you an introspective blog on what life has been like these last few months, on how I’ve grown in my faith and the ways that I’ve changed. But I’ll save that blog for another day. 😉

Instead, I’ll give you a fun bullet-point blog, on the interesting and funny things these last six months have held. Hopefully these bite-sized stories will help you share a little bit in my unique sense of humor, in the shocks and the fascination, and in the joy of experiencing new things.

A gecko lives in my room, and another in the bedroom across the hall. I talk to him now and again to thank him for eating the mosquitos that eat me. Maybe Africa has messed with my brain a bit too much. 😉 The first gecko I met, I named Moki. The gecko in my room got the name Loki. So, naturally, his brother across the hall got the name Thor. Every once-in-a-while these geckos get to catch some of my musings as I’ve adjusted to life in Africa. I like to think they’re becoming a bit wiser from the things they hear, but perhaps more likely, they’re just entertained by my foibles. These are some of the events they have borne witness to.

So, now you know what my geckos know, and you can make up your own mind whether they’re entertained or confounded. Regardless of your evaluation, you can be sure these six months have been full of quite a few entertaining stories.

Time is funny.

Einstein told us time was relative, that it depended on fixed points, speeds, and movements for time to have any sort of meaning. I have certainly felt its relativity these days. Life is on the move. I’m in transition. A few days here, a few weeks there, Christmas back with family, and then Africa. Until I move into my house in Uganda, I won’t be in any one place long enough to collect dust.

That move still doesn’t quite feel real to me. I am excited for it. I’m praying about it. I’m trying to learn and prepare as much as I can before I go. But I’m in limbo. I’m not settled in Africa yet, but I already feel out of place in Oklahoma. And the time…

Time doesn’t come for me in seconds, minutes, days, or weeks anymore. It seems to move very differently, in different intervals. The units of measurement for time aren’t hollow seconds, but meaningful rhythms and patterns. How long has it been since I saw North Carolina friends? Well, as long as those daisies sitting in my vase have lasted. How long until I move? Only so many more hugs from Dad, or heart-to-hearts with Jacob, or episodes of a favorite TV show with Mom. How many hours have I driven to see friends and family? That’s measured in the number of audio books I’ve listened through. How long until I leave for training? That’s counted in how many churches I’ve gotten to visit and share with.

Time has a way of telescoping for me recently—of stretching out and shrinking up in the most unreliable ways. The few short minutes it takes to drink in exactly the way the mist hangs over damp Oklahoma oaks in a purple dusk will stretch to years in my memory until time brings me back to Oklahoma and gives me the chance to see it again. Time totally stops when I pull up the car just to take in the exact way the bronzy Oklahoma twilight reflects in still puddles across a gravel backroad. And yet whole days vanish as I try to pack and sort and check off items on a very long to-do list.

Time right now feels less like a certain quantity of days until I move and more like a certain number of brilliant starry nights with a fresh Fall wind and the Milky way overhead, a certain number of those signature Oklahoma sunsets that stretch and stretch over the fields for miles just until they break and the fiery sky snaps into dusk, a certain number of last hugs with friends, last tears at parting, last goodbyes.

And all the time, Africa is calling.

As I pack up my life here and bring things to conclusion before I leave, I find my mind increasingly often faced towards Africa, contemplating the new life there, the new favorite sights, sounds, faces, hugs. Between all my lasts and my unreliable measurements of time, Africa looms larger and larger, rushing the days past me, but stretching them out with tasks of conclusion and preparation.

Paul wrote to his Ephesian brothers and sisters, “Look carefully then how you walk, not as unwise, but as wise, making the best use of time, because the days are evil.”

There’s quite a bit in that to calm and comfort me during this transition. If I face these days wisely, counting them in whatever ways I can, making the best use of my times however short or long, I will walk as a child of the Light, in goodness and truth, and I will please my Lord. That’s what Paul says in Ephesians 5. And he says that the days can be evil—can rush on by without anyone the better off for them unless…

Unless I redeem my time, soak in all the rest, the preparation, the fellowship, the experiences of the Lord’s faithfulness.

Moses was somewhat of an authority on time himself, having lived through a lot more of it than we will, and experiencing quite a few transitions himself. In psalm 90 he muses on what he had learned. Our days can be like grasses, he says, fresh in the morning and withered by evening. “We bring our years to an end like a sigh,” he says.

Wow. What a picture. How many of my days end like a sigh? That sounds like such a tragedy in light of the joy we can have in our Lord and the pleasure we can have in the days he has given us. “So,” Moses says, “teach us to number our days that we may gain a heart of wisdom… Satisfy us in the morning with your steadfast love, that we may rejoice and be glad all our days.”

If we want to redeem our time, we must count our days, make them count, fill them with joy in the Lord’s presence, squeezing all the good we can out of our days instead of letting them rush on and end like a sigh. That, Paul and Moses say, is a wise way to live.

So as these crazy days come to a close, as my transition comes nearer, I hope you will find me, dear friends, counting my days, redeeming my time, and making the best use of them. With the Lord and his wisdom, my days may be full and joyful, not a bit wasted or sighed away.