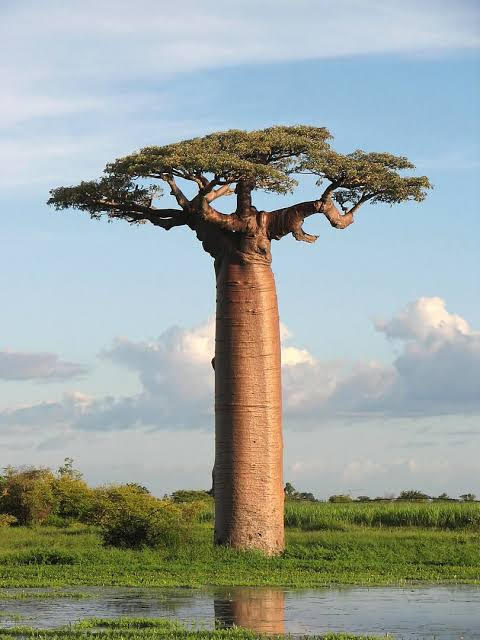

The book, “The Little Prince” nurtured my fascination with baobab trees. This short, remarkably deep children’s book is about a boy who lives on his own, tiny planet. Every morning the boy washes and dresses, then tends to his planet. He determines the sprouting roses from the baobab shoots and uproots the dangerous trees. The little prince explains:

A baobab is something you will never, never be able to get rid of if you attend to it too late. It spreads over the entire planet. It bores clear through it with its roots. And if the planet is too small, and the baobabs are too many, they split it in pieces.

That same image of crushing, constricting roots comes to mind when I read in Hebrews 12 about a bitter root that can grow up among the people of God to bring trouble and defilement.

Hebrews 10 gears up with a discussion on perseverance in the face of suffering. It outlines how, because of Christ’s sacrifice and redeeming work on our behalf, we can endure suffering with the body of believers at our side. Together we can stand our ground because we share a faith in the unshakeable Faithful One.

Chapter 11 follows with an incredible tapestry of stories to demonstrate this kind of faith. Believer after believer was considered faithful because they were sure of what they hoped for and certain of things not yet seen. The author says that this kind of faith is necessary to please God. Faith is what draws us to him because it means we believe two things: “that [God] exists and that he rewards those who earnestly seek him.” In shorter words, faith is the belief that God exists and that he is good.

These stories demonstrate that faith is strongest when it endures uncertainty and lack of evidence that God does exist or that he is working good when we can’t see it. According to this chapter, faith is being certain of what we do not see (that God exists), and sure of what we hope for (that God is good). The Bible characters in this chapter show with their lives that faith means knowing God’s good plan is often bigger than you can see or understand, but believing it anyway.

Chapter 12 shifts from describing the faith of believers who went through suffering to a discussion on how the Lord disciplines us through that suffering. “Endure hardship as discipline,” the author says, because “God is treating you as sons.” We are told this discipline will be painful, but that it produces a harvest of righteousness and peace.

The discipline of a loving parent takes a moment of disobedience, hardship, or suffering, and turns it for their child’s good. True discipline is the gift of a teaching moment, used to build good character out of bad circumstances. God does the same for us because he delights to call us his sons and daughters. Because of this, we can understand any suffering that we endure in faith as discipline for our good.

If we keep in mind the truths that God exists and he is good, that his plan is perfect but bigger than our ability to understand, we weather suffering well. This is what the author means when he or she writes, “See to it that no one misses the grace of God and that no bitter root grows up to cause trouble and defile many.” If we miss God’s grace—if faith does not guide us to see our suffering as loving discipline—we grow a root of bitterness instead of the harvest of righteousness the chapter promises.

This shortsightedness springs from a lack of faith in God’s good plans, and it grows in us a crushing root of bitterness that slowly tears us and our fellow believers apart. But as the author has already explained, faith is the perfect antidote for this poisonous root of bitterness. The chapter goes on to hold up Esau as an example of bitterness, because he gave into his appetites and gave away his inheritance for a single bowl of food.

When we focus on our appetites and desires, instant gratification becomes our goal. Like Esau, we want to alleviate temporary suffering with something the world has to offer. If we focus on the heaviness of our suffering instead of the grace God gives to discipline us through it to a better end, we give up our inheritance like Esau. We no longer receive discipline as a son because we have cast aside faith in God’s far-sighted plan in favor of short-lived satisfaction. This vain effort to avoid the suffering God has given us will always leave us unsatisfied. And so grows the root of bitterness in place of what could have been a harvest of righteousness and peace.

In the story of Ruth, we meet a woman who defines herself by her bitterness. After fleeing her country because of a famine, Naomi lives as a refugee in Moab. While there, her sons marry local women, but Naomi can’t catch a break. Before long she has watched not just her husband, but both of her sons die.

Her life is emptiness. She left her homeland when it was empty of food. She was soon emptied of her family members one by one. She decides to try her luck by returning home and tells her daughters-in-law to remain in their land and let her go on alone. When they protest, she tells them her womb is empty because her bed is empty and she could never give them another husband. One daughter-in-law, Ruth, stubbornly remains with Naomi. But when the two reach Naomi’s home, she tells the eager neighbors not to call her by her old name.

“Don’t call me Naomi,” she told them, “Call me Mara, because the Almighty has made my life very bitter. I went away full, but the Lord has brought me back empty. Why call me Naomi? The Lord has afflicted me; the Almighty has brought misfortune upon me.”

Naomi sees the brokenness and emptiness in her life and blames it on the Lord. She chooses a new name that means ‘bitter’ and gives witness to the whole town that she blames the Lord for her suffering.

But now listen to the story told another way.

The Lord had a sovereign plan for Naomi and her family line. Instead of letting them starve and die in a season of scarcity, the Lord prompts them to leave for greener pastures. While in this foreign land, the Lord grows Naomi’s family with two daughters-in-law, one of whom is very devoted and compassionate. Through continued adversity, Naomi and Ruth’s bond grows so much that when given the opportunity, Ruth decides to leave the only land, people, language, and religion she has ever known to throw in her lot with Naomi.

God prepared a relative to marry Ruth, continue the family line, and care for Naomi as she ages. Even as Naomi proclaims her bitterness at the Lord’s treatment of her, the land around her was ripening for harvest: “So Naomi returned from Moab accompanied by Ruth the Moabitess, her daughter-in-law, arriving in Bethlehem as the barley harvest was beginning.”

God showed grace and filled Naomi’s life even as she chose to focus on the emptiness. He filled her home with food and her heart with hope, even as greater fulfillment awaited her. By the end of the story, the Lord has filled Ruth and Naomi’s home with a man, Ruth’s womb with a son, and then Naomi’s lap with a grandchild.

The same bitter root Hebrews mentions grew in Naomi’s heart. Her name means ‘pleasant,’ but she was anything besides pleasant to be around as bitterness took root in her heart. By the end of the story, she has learned faith. She learned to trust the Lord’s goodness in her life so she can set aside her bitterness and have faith in a greater plan she cannot see. Uprooting her bitterness was less about a change in situation (her husband and sons were still dead, and no happy ending for Ruth could change that), and more about a change in perspective. By the end of the story she chose to focus on the Lord’s goodness rather than her misfortune, and it relieved her of her bitterness. She did not miss God’s grace in her suffering.

Yet another Old Testament story illustrates this point. In a stark contrast to his brother Esau—the example of the bitterness Hebrews warns against—Jacob dealt with adverse situations quite differently. In Genesis 32 he found himself preparing for a confrontation with a vengeful brother, and afraid for his life. He sent a caravan of all his worldly possessions and family members on ahead and decided to spend the night alone. But the Lord came to him and they wrestled all night. On top of his emotional anguish, he was in physical pain from a dislocated hip, and exhausted from grappling with an opponent too powerful for him.

Jacob doesn’t give up or complain. He doesn’t focus on his own appetites or desires like hungry Esau did when face with lentil stew. If Jacob had chosen to focus on his own suffering, he would have just given up, especially when the man asked for an end to the tussle at daybreak. Instead, Jacob refuses to let go until the Lord blesses him.

Jacob knew so little about God at this point in his life, but he learned experientially about the Lord’s power, goodness, and grace from this encounter. He refused to give up the conflict until he had been blessed, and so instead of choosing to respond to suffering with bitterness, he responds with endurance until he achieves the goal. The Lord blesses him and gives him a new name, “Israel,” which means ‘struggles with God,’

Like Jacob, like Naomi, like Esau, our lives are all kinds of messy right now. We struggle with depression, with lockdown, with fears or anxieties about Covid-19. Our lives have been disrupted. We’ve been locked inside. We’ve faced separation from friends and family and our church body. Maybe we’ve lost jobs or just moved or our lives have changed so much because of the pandemic we don’t know which way is up or even what ‘normal’ we could return to anymore.

On top of that, we grieve and protest injustice in the States. We face disillusionment and feelings of defeat as we fight an uphill battle against broken systems. We’re heartbroken to face the realities that these broken systems created by sinful humans exist not just in our government but in our communities and churches and workplaces, no matter where we live in the world. We are exhausted. Our bodies feel the physical toll of stress. We struggle to find hope, and maybe faith in the unseen is that much more difficult as we feel surrounded and soaked in suffering.

In the face of these afflictions we have two options.

Like Esau, we can choose to live by our appetites, miss the grace of God, and try to satiate our hunger or pain with a quick fix without thought to the future. But if we seek to satisfy our needs with anything less than eternal, we will always hunger and thirst again. If we choose like Esau to focus exclusively on our immediate suffering, we can only increase our frustration as temporal solutions fail again and again and again. As we watch the world and its offerings fail to satisfy us, we can only become bitter. The root grows in us and constricts our soul, crushes our spirit, and breaks our heart.

Or, like Jacob, we can persevere. The struggle and suffering we experience now has the reward of blessing on the other end, if we persevere. The blessing is becoming the new man Paul talks about in Colossians, with a new name John promises in Revelation. If we choose endurance and faith over bitterness, like Jacob, we can know the face of God more clearly for having grappled in his presence, and we are changed. The difficulties we’ve experienced and will continue to experience are not only uncomfortable and painful. There are very real rewards on the other side of the suffering. Like Jacob, we can ask the Lord for blessing to come out of our struggle, and He has already demonstrated that he can and will honor such requests. God gives the blessing freely, but the price we must pay is endurance. We must endure even with all the fear, pain, suffering, exhaustion, and ignorance of God the struggle reveals in us.

Naomi’s story shows us there is still hope if we have already given in to bitterness. If we realign our perspective and choose to focus on the Lord’s goodness instead of our emptiness, he will fill us with his presence, the greatest gift of all.

Let us with the saints choose faith in the Lord’s goodness over short-sighted bitterness. Our confidence will be rewarded and when we have persevered, we will receive the promise. By God’s grace and our certainty in his faithfulness, we will not be those who shrink back and are destroyed, but those who believe and are saved.