I wish I could bring you all with me when I go to the mountains, so you could see what I see and hear what I hear. But this time someone joined our group with a photographer’s eye and a camera to channel it. I’ll throw in some of his pictures below, but I wanted to give you some “mental snapshots” to go with them—thoughts and moments I’d always want to remember if I never saw this place or these people again.

Sundays on these trips are different days. They brim with activity like every other day, but they’re unpredictable and often lead to unexpected adventures. Every “teaching” day I wear a more comfortable dress and headwrap, balancing cultural respect with functionality. But on Sundays I break out the Sudanese cultural dress, a toub. Meant to be worn over a full set of clothing, this long piece of fabric wraps multiple times around the body to cover legs, torso, arms, and hair in one unbroken block of color or vibrant pattern. I don’t have to teach or lead on Sundays, so my decreased maneuverability and comfort in the sometimes 7-layer getup is an acceptable sacrifice to make for all the sweet smiles from strangers who can see my clothes, hear my Arabic, learn my local name, and immediately understand I value them and their culture.

This Sunday I don an all-black under-layer of leggings and a long-sleeved leotard, so nothing will bunch or twist under the layers of toub wrappings. Then I choose the tie-dye purple and green toub that’s more gauzy and breezy than some—a gift from a friend used to wear it herself in hotter desert conditions than this. When everyone is ready for church we cut across a couple fields, tramping on the footpath I could never have picked out for myself while hiking my layers up so I don’t drag half a field of dried grass and stickers into church with me. We arrive and worship with our brothers and sisters through a beautiful service in a simple building decorated with fresh-picked local flowers hanging from the roof supports. A few holes and pockmarks in the walls from the last war’s aerial bombardment makes the building an even more beautiful testament to God’s protection.

As we mingle in the yard after church the typical jokes follow about my positive marriage prospects if I keep wearing a toub, and theatrical surprise played for laughs at my Arabic comprehension when someone suggests a son or a nephew who might be about my age. Laughing, I hold the pumpkin our teammate was given as thanks for sharing the sermon today, and clumsily try to balance it one-handed on my head to demonstrate the poor excuse I’d be for a working Sudanese wife. As we walk back home I unwrap one torso-encumbering layer of the toub and re-wrap it to throw it over my shoulder in a less formal style women wear when they have work to do. I’ll wear it that way for the rest of the day for greater ease of movement. After lunch, a friend calls out “hey Kandaka!” as I pass by. He’s teasingly comparing me and the toub over my shoulder to the iconic 2019 Sudanese Revolution picture of a woman called Kandaka. She herself was named that after the long Sudanese historical tradition of female leaders and cultural nurturers who moved and shaped a people with their stories. You’ve likely read about a Kandaka (or Candace) in Acts 8. A crooked grin immediately splits my face at the flattering comparison, and that I caught the deep cultural reference.

Not long after a relaxed Sunday lunch, we’re given a few minutes’ warning before a trek to go see a building site for a hoped- and prayed-for new Bible college. Unsure of how long the trip will take, I wad up my body and my layers in the half-seat above the gear shift in a truck older than me, sandwiched between the driver and my teammate for what turned out to be a three hour excursion. The bed of the truck is a clown-car of people, and two motorcycles flank us carrying those who couldn’t cram into the truck bed as we drive through gardens and dry river beds up to the crown of a mountain. We clamber around on the mountaintop for a while and pray over the site before we descend to explore the flash flood river bed and the new springs that opened up last rainy season.

It was with pride that I managed almost as well as a Sudanese woman would in her own dress, and only caught my layers once on some fallen acacia thorns. In the dry riverbed valley below the brow of the hill, we see a baobab trunk that was swept down in last season’s flood. I still haven’t gotten over my giddy excitement of seeing these massive, distinctive-looking trees for the first time in my life in this area, so I rush down to feel its smooth, cool bark and branches I could never reach in standing trees. The youngest guys clamber up the side of the massive fallen trunk, and I know instantly I can’t miss this opportunity. With a moment to assess the physics involved, I kick off my flip flops and flex my toes in the sandy pea gravel underneath my feet. I hike up my layers and to accompanying shouts of “Go slow!” and “Don’t let the white woman fall!” I hop up the side of the ancient tree, using gnarled knots in the bark for hand and foot holds, with my skirts gathered in one hand. Everyone nearby swarms back up the tree and poses for a picture with the white girl in the local dress who miraculously avoided face-planting.

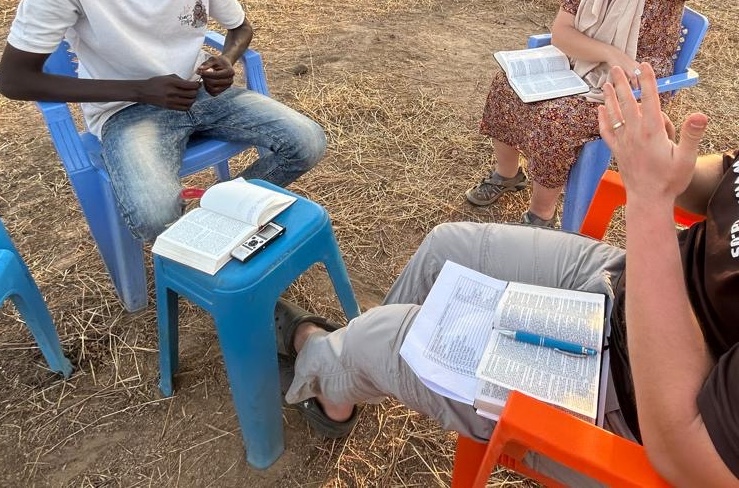

Toward the end of the week, I sat again under the same patchy shade of the same scraggly tree with the group of two young men. One has faithfully shown up to work every time we’ve visited. He’s my youngest brother’s age, and he knows me by my Arabic name that means “big sister.” This time we’re listening to the story of the woman caught in adultery from John 8 through translation from their language to Arabic. Every detail is accurate, and spit out in quick succession. Another deep story about how Jesus interacted with women who were publicly shamed, rattled off like a speed recitation.

I take a beat to compose my thoughts and decide where to start to both compliment their good work and encourage them to go deeper and tell the story with more faithfulness to all those layers. But I didn’t have to worry. Perhaps more comfortable after we talked through some taboos earlier, my “little brother” blurts out, “where was the man?” A slow smile grows on my face as he continues. “If she was caught IN adultery, there must have been a man. Why didn’t the religious leaders bring him in too?” He has some theories that he rattles off, and I offer some more. But we dig into the story so he can see the way the religious leaders brought the woman there as bait for a trap for Jesus, to try to get him to say something against Moses and the Old Testament law.

But I go back to some of the details in the story that explain some things between the lines. Miraculously God gives me the Arabic I need to communicate the nuance of this story. But I still don’t have the vocabulary to communicate the complex web of shame in this story that translates directly into these two young men’s culture. I explain that the story begins at sunrise, and how it was possible the woman was caught and brought in some state of undress when she was paraded out in front of everyone there at the temple to worship. I readjust the part of my headscarf hanging down over my torso, matching the unconscious expression of any local woman who feels exposed emotionally or socially. I hope my actions and gestures fill in for some of the nuanced vocabulary I’m missing, but before I know it, I’m up on my feet to explain the story spatially.

When the religious leaders brought her into the temple, they treated her like she was only an object for their trap for Jesus. To answer the original question, they’re obviously thinking about incriminating Jesus more than incriminating the man she was caught with. But in the process, they make her the object of everyone’s attention. I stand in the middle of the circle, pulling my headscarf to cover more of my body. But then they ask Jesus, and not only does he take a long time to answer, he bends down and begins mysteriously writing in the dirt. I grab the shoulders of my American teammate, to use him as a stand-in for Jesus. Jesus could have immediately given them a wise answer, but he delayed. I step out of the circle and stand behind my teammate, with him between me and the young men. Now, everyone at the temple was looking at him and waiting for an answer. He was covering this woman and her shame, even though she had sinned. And not only that, he took some of the shame from her. When he didn’t answer, everyone looked at him and wondered if he could give a wise answer or if the religious leaders would humiliate him.

We continued telling the story with me walking through its paces, showing that Jesus chose to forgive this woman’s sin instead of condemn it, and to cover her shame instead of expose it. At the end, the young men had huge grins on their faces because they saw how Jesus has not fallen in line with heavy cultural shame directed toward women, but turned it on its head in order to protect them. I was glowing inside at the chance to be their big sister and tell them things other women aren’t socially allowed to. I was honored and humbled to help disciple them through the cultural expectations they face, so they can break the mold and be better brothers and fathers and husbands one day.